Back to

Table of Contents2

To next page

Li Fang: Taiping Guangji (980)

(Copious Records from Tai-ping) Tai-ping means Great

Peace.

------------------------------------------

The Taiping Guangji 太平广记; is a collection of stories compiled in the early Song dynasty under imperial direction by Li Fang. The work was completed in 978 and printing blocks were cut but it was prevented from publication on the grounds that it contained only xiaoshuo (fiction or "insignificant tellings") and thus "was of no use to young students." It survived in manuscript until it was published in the Ming dynasty. It is considered one of the Four Great Books of Song.

Taken from: Chang Hsing-long, "The Importation of Negro Slaves to China under the Tang

Dynasty (A.D. 618-907)," Bulletin of the Catholic University of Peking Vol 7 (1930)

Also called Tai p'ing kuang chi/ Tai ping guang ji/ Tai Ping Guang Ji

This is a link to some other pictures of statues of Kunlun people found in graves in the

Tang capital.

Tao Hsien purchases Mo-Ho; Ink sketch by Ch’en Hsu; Department of fine arts Catholic University of Peking

Beginning 20th century. I do not know in what edition this picture has been used

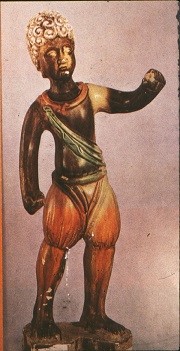

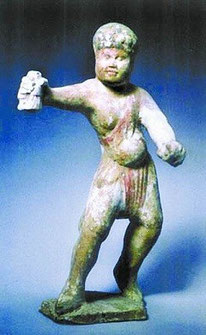

This figurine, (one more kunlun figure) was discovered in 1954 by Chinese archaeologists working in the old Tang capital of Chang’an (modern Xi’an). It was buried in the tomb of a lady who died AD 850, and is thought to represent an African servant who attended the lady in life.

In this book are reproduced the Chuanqi tales (fantastic story) written by Pei Xing (850-900) and others.

Although most black slaves must have had a South East Asian origin it is impossible to say if some where not African. The Chuanqi tales are mentioned here only because so many authors decided

that the black slaves in these stories must be African.

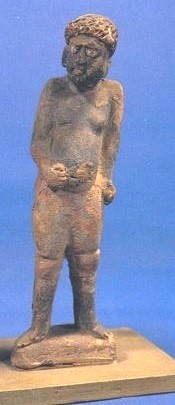

Probably E Han 25 - 220AD . This jade artefact is in the form of a nude youth with curly hair and un-Chinese features (known in Chinese history as a "Kunlun slave", meaning a menial from the far west). The circular tray, is the oil dish of an oil lamp.

A scene from: T'ai-p'ing Kuang Chi (Book CXCIV) Record of K'un-lun Slaves

T'ai-p'ing Kuang Chi (Book CDLXIV treating of aquatic creatures) also found in Liu Hsun’s Ling Piao Lu Yi

(Record of Strange Things beyond the Southern Mountains):

When the former Minister of State Li Teh-yu was degraded and banished to Chao-chou, his boat was damaged while passing over O-yu-t'an (the "Shallows of the Crocodiles") and many of his valued

treasures, old books, and pictures fell into the waters: whereupon he bade a K'un-lun man dive into the water in search of them. The latter. however, perceiving the exceedingly large number of

crocodiles that swarmed in these shallows, was afraid to make the attempt (the place being notorious as a haunt of crocodiles).

T'ai-p'ing Kuang Chi (Book CXCIV, treating of chivalrous and doughty deeds). Also found in the Ku Chin

Shuo Hai, the Shuo Yuan, the T’ang Jen Shuo K'uai, the Chien Hsia Chuan, and the K'un-!un Nu Chuan.

("Record of K'un-lun Slaves): "During the Ta Li period (A.D. 766-779) of the T'ang dynasty there was a young man named Ts'ui whose father was a famous mandarin and

a personal friend of the Chief Imperial Astronomer Yi P'in. When Ts'ui was a Ch'ienniu Mandarin, he visited Yi P’in who was sick. Now Ts'ui had a complexion like unto jade. He was of a calm and

retiring disposition: his demeanor was placid and courteous and his accent was distinct and cultured. When he reached his destination. Yi P'in ordered a singing girl to lift the door-curtain and

bid him enter. After Ts'ui had communicated the greetings of his father and paid the customary homage to his host, Yi P'in, who became charmed with the young man's appearance, invited him to sit

down for a chat. In a little while three singing: girls of extraordinary beauty entered the room, the foremost carrying a golden bowl full of pink peaches, which she peeled and sprinkled with

sweet milk. Yi P’in then ordered one of the girls who was dressed in a robe of red silk, to serve the peaches to his guest in a small bowl. Ts'ui, who by reason of his youth was exceedingly

bashful in the presence of the girls, declined to partake of the proffered fruit. Thereupon Yi P'in ordered the girl in red to feed him with a spoon. Ts'ui was forced to yield to such insistence

and the girl smiled at him on taking her departure. When Ts'ui finally took leave of his host, the latter said: 'If you can bear with the company of an old man like myself, you must by all means

come again whenever you are at leisure. The girl in red was again ordered to attend on Ts'ui's departure. As he was leaving he looked back for another glimpse of the girl and saw that she held up

three fingers, and that turning her hand three times she pointed to the small mirror on her breast saying: Remember. Thereupon she withdrew without further ado. Having reported the result of the

visit.

Ts'ui retired to his study. During the ensuing days he was absent-minded and listless, his words were few, and his face assumed a far-off expression. For hours he would sit and brood, and he lost

all appetite for food. However he then composed a poem, which runs as follows:

In my wand rings I strayed

To the top of P'eng-lai,

'Where a jewel girl I found

With eyes like the stars;

When thru the vermillion gate half-closed

The moonlight floods her palace court.

May it cause the flower-sweet,

Snow-white maid to think of me.

All the servants were alarmed at the condition of their young master. At that time there was in the household a Kun-lun slave named Mo-leh who observed him closely and said: (What have you on

your mind? Why do you act like one distraught with some great sorrow? Why not give your confidence to me, your old slave?' Ts'ui made answer: 'How could an uncouth fellow like you appreciate that

which is in my heart?' 'But tell me anyway,' said Mo-leh, and I shall find a remedy for your troubles, be they present or future.' Ts'ui, greatly impressed by the assurance of the slave, made a

full confession. Whereupon the latter declared: 'That is an easy matter. Why did you not tell me sooner and save yourself much worry?' When Ts'ui asked him to explain the signs made by the girl,

Mo-leh replied: Why should they be hard to interpret? When she held un three fingers she meant that she dwells in the third of the ten courtyards that Yi P'in assigns to the singing girls. When

she turned her hand thrice, she meant fifteen, that is, the fifteenth of the moon. By pointing to the small mirror, she meant a night when the moon is full. In other words, she wanted to make an

appointment with you.'

On hearing this Ts'ui was overcome with joy and ecstasy. 'What plan,' he asked, would you suggest for attaining my heart's desire?' With a smile, Mo-leh answered: The night after next will be the

fifteenth night. Pray dye two pieces of silk to a dark hue to make a vesture for Yourself. In the house of Yi P'in there is a ferocious hound that guards the entrance to the courtyards of the

singing girls and is sure to kill anyone who attempts to enter. This dog is as clever a-s a demon and as fierce as a tiger; it was bred at Menghai in the district of Tsao-cbow. None in the world

save myself is capable of killing this dog, and I shall kill it tonight.' After Ts'ui had feasted the slave on meat and wine, the latter departed taking with him a chain and a hammer. After the

space of a meal time he returned and said: The dog is now dead, and we shall meet with no obstacle.' At midnight on the appointed date, Mo-leh bade Ts'ui don his dark attire and lifted his master

over the wall, which was ten li in circumference. Thence the two made their way to the courtyards of the singing girls and stooped at the third gate, which they observed to be ajar revealing a

dim light within.

When they entered they heard the singing girl sigh and noticed that she sat as though waiting for some one's arrival. Her lustrous hair was somewhat disheveled, her countenance slightly flushed,

and she looked very sad and forlorn. As they watched her, they heard her sing the following lay:

'Like an oriole in some lonely vale

Seeking its mate with plaintive note,

My jewelry I cast aside and

Steathily creep ‘neath the blossoms:

But the azure cloud is wafted away

Without leaving behind any token:

Despondent I lean on my flute of jade

And envy the bliss of the Phoenix.

It was an hour when all the watchmen were asleep and when everything was quiet and silent. Finally Ts'ui lifted the curtain and entered her room. The girl

remained motionless gazing at him for a long time. At last she sprang up from her couch and seized Ts'ui by the hand saying: 'I knew that your wit was keen and that you would interpret aright the

signs: which I made to you. But I never anticipated that you would respond with such alacrity.' Whereupon Ts'ui told her all about Moleh's cunning and how he had made it possible for his master

to scale the wall. 'Where is he?' she asked, and he replied: 'Standing outside.' Thereupon the girl bade Mo-leh enter and gave him wine in a golden goblet. Turning to Ts'ui the girl said: 'My

home is in So-fang. I was the ward of a general who compelled me to become a singing girl. I have often wished I were dead but have never had the courage to take my own life. Though my face may

seem fair and radiant, yet my heart is oppressed with heavy sorrow. Though I eat with chopsticks of jade and drink from golden goblets; though I am surrounded with magnificent screens and clothed

in the finest cloth; though I sleep on a silken couch inlaid with pearls and precious stones: yet all these things, far from giving me happiness, make me feel as if I were a prisoner.

Since your noble body-servant is endowed with such extraordinary prowess, will you not easy to rescue me from this captivity? If you but harken to my prayer, I will rejoice to become your humble

handmaiden and will die so with out regret. Pray suffer me to bask in the light of Your countenance' Lo I am eagerly awaiting Your reply !' "As Ts'ui stood silent and irresolute. Mo-leh spoke up.

Since the lady,' said he, 'has made up her mind, it will not be hard to fulfill her wish.' The maiden was overjoyed at this reassurance. Mo-leh requested her to pack up her clothing and other

gear, which he carried out in three trips. Returning from the third trip, he warned them of the approach of dawn. Then picking up both Ts'ui and the girl, he vaulted with them over the wall

and ran off carrying them on his shoulders for a distance of ten li. As none of the watchmen noticed what was going on, the trio reached Ts’ui’s home in safety and there they concealed the girl.

"Yi P'in's household did not become aware either of the girl’s absence or of the death of the dog until the following morning. Yi P’in was then greatly alarmed and exclaimed: The seclusion of my

gates and walls has been hitherto inviolate, every means of ingress being barred by bolts and locks. The intruder would seem to have been a winged being, for he has not left behind a single

trace. He must forsooth be a knight of stupendous prowess. Do not noise the matter abroad. lest perchance we incur some further misfortune.' After the girl had lived in seclusion with Ts'ui for

the space of two years, she ventured forth in blossom-time riding on a cart to Ch'u-chiang. There she was recognized by one of Yi P'in's servants who duly reported the matter to his master. Yi

P'in in his surprise summoned Ts'ui and questioned him closely. Ts'ui in his fright made a full confession, describing Mo-leh's part in the affair. Yi P'in said: The girl has indeed been guilty

of a great offense. Inasmuch, however, as she has lived with you for more than a year. I will overlook the matter; But touching the complicity of Mo-leh, I must needs put an end to him; for he is

a public menace.' Whereupon Yi P'in ordered fifty mail-clad soldiers, all armed to the teeth. to surround Ts'ui's house for the purpose of capturing: Mo-leh. Whereat the latter, snatching

up a dagger, vaulted over the wall, seeming to his Pursuers like some, winged being endowed with the speed of an eagle. They let fly at him a veritable shower of arrows but none of these could

reach him. An instant later he completely vanished from view. This feat not only astounded Ts'ui but terrified Yi P'in as well, causing the later to rue bitterly the rash step he had taken.

Thenceforth Yi P'in was wont, when he retired at night, to surround himself with a guard of servants armed with swords and spears. And he continued this practice for a whole year before he

finally gave it up. After an interval of more than ten years one of Ts'ui's servants, on a visit to Loyang:, saw Mo-leh selling medicinal herbs in the market-place. Time had not availed to change

his appearance in the least.

T'ai-p'ing Kuang Chi, (Book CDXX which treats of dragons). Also found in the

T'ao Hsien Chuan ("Biography of T'ao Hsien) by Hsien-Chi-tsi

T'ao Hsien was a descendant of T'ao Yuan Ming (a famous scholar of the Chin dynasty), the magistrate of P'eng-tseh (in Kiangsu). During the T'ai Yuan: period (A.D. 713-741) he lived at K’un-shan

(in Kiangsu). He owned vast lands and rich merchandise. Having set over his affairs and possessions an honest and capable servant, he himself left home to wander about the country and was not

infrequently absent for periods covering several years. He did not even know the names of his grown up sons and grandsons. So great was his scholarship that he might have been a mandarin of the

highest rank, but he never sought political preferment, alleging that he was too careless and irresponsible for such a calling. He was also an accomplished musician and had an exceedingly

sensitive ear. Those who knew of his gift tested it by means of tiles the date of whose baking they had recorded. When such tiles were struck, he was able to tell their exact age from the sound

given forth. Moreover, he was the author of a treatise on music. He personally designed three boats of great beauty and exquisite workmanship. One of them was for his own use, another for that of

his guests, while the third served as a floating pavilion for social gatherings. Among his guests were the Doctors of Literature, Meng Yen-shen and Meng Yu-ch'ing, and the commoner Chiao Sui,

together with their respective wives and servants. T'ao Hsien had a chorus of singing girls who were very talented in music. So manned, his three boats visited various parts of the country to

take in the scenery. Such trips were made mostly in spring-time. Since the name of T'ao Hsien was known at the Imperial Court and the times in question were peaceful, he was welcomed by the

officials of all the cities that he visited. But he generally declined their hospitality saying: I am a simple rustic and quite unworthy to be the guest of princes and nobles.' Occasionally,

however, he would stop where he was not invited. The people of Wu (S. Kansu) and Yueh (N. Chekiang) called him a water-genius because water-genii are believed to have no fixed abode and are wont

to inhabit any stream or mountain. Having a relative who was then the magistrate of Nanhai (Canton), T’ao went thither to visit him. This magistrate was so flattered by the visit of one who had

come from such a great distance that he gave T'ao a million cash. With this sum the latter bought an antique sword which was two feet in length, a jade bracelet four inches in diameter, and a

Kun-lun slave named Mo-ho, who had belonged to a trading vessel and who was an expert as well as daring swimmer. These possessions,' said T'ao, will become heirlooms in my family.' "On his return

journey T'ao Hsien entered the Peh River (Peh-kiang) by way of Pai-cheh. As the water was remarkably clear, he dropped the sword and the bracelet into its limpid depths, ordering Mo-ho to dive

for them. As this sport gave him a delightful thrill, he repeated it on many occasions in the course of ensuing years. Once as he was sailing on Lake Ts'ao (Ts'ao Hu in Anhui), he again dropped

into the water the sword and bracelet, and ordered Mo-ho to dive for them. In the twinkling of an eye the slave reappeared from the depths holding aloft the sword and bracelet, but he informed

his master that he had been bitten by a poisonous snake and obliged in consequence to cut off his finger in order to save his life. On hearing this Chiao Sui said: Mo-ho has been very, likely

wounded by some spirit of the deep; for those who dwell in the waters do not tolerate the inquisitiveness of men. Whereupon T'ao Hsien replied: I respectfully bow to your judgment, but I must

needs own a certain admiration for the sentiment of Hsieh K'an-loh who said: Even death shall not avail to rob me of my joy in the scenery; I suit my own pleasure forgetful of all else. To

sojourn in inns and taverns, to be borne to all places, to be attired in the clothes of a commoner, to enjoy the companionship of cultured fellow-travelers, and to have roamed about for thirty

years according to the dictates of my fancy: such is my destiny. But to ascend the jade staircase (i.e. to become a mandarin of high rank), to have audiences with the Emperor, to render signal

service, to be rewarded with high honors, and to see the fulfillment of every ambition: that is not the supreme goal to which I aspire.' Thereupon he ordered his boats to weigh anchor saying:

'Let us pay a visit to Hsiang-yang Shan before returning to the capital of Wu (Soochow).' When they reached Hsi-seh Shan, they cast anchor before a Buddhist temple called Chi-hsiang. Observing

that the waters were dark and stagnant T'ao exclaimed: 'Verily some monster must lurk in these depths !' Whereupon he again threw in the sword and the bracelet bidding Mo-ho dive for them. The

latter having vanished beneath the waves did not reappear for a long time. When he rose again he was gasping like one in the throes of death, and coming on board was too weak to stand on his

feet. He reported his experience as follows: I was not able to recover the sword and the bracelet because they had chanced to fall at the feet of a gigantic dragon twenty feet in height. Whenever

I attempted to draw nigh to the sword and bracelet, the dragon gave me an angry scow..' T'ao replied: 'Yourself, the sword, and the bracelet are my three treasures. Now that two of them are lost,

of what use are you to me? Do your utmost, therefore, to recover them.' Having no alternative but to dive once more, Mo-ho unbound his hair, uttered a fearful yell, and with tears of blood

exuding from his eyes plunged headlong into the waters, never to reappear. After a long while fragments of his body floated up to the surface, a mute reproach, as it were, to T'ao. At this sight

the latter began to weep bitter tears and gave orders to sail home forthwith. From that time on he ceased to roam about the country and staid at home instead, devoting his time to writing poetry.

One of his poems is quoted below:

'Who was there to watch with heedful care over my home and estate ?

Serene is the life at my new abode ensconced in the Land of Wu-yueh,

Yet not till my hair had turned to gray did I find its peace again.

Descrying the hills in the distance blue I reckon the miles to my home.

The stork shakes the leaves on the maple bough as sinketh the sun at even;

The crane stands erect 'mid the flowering reeds while sparkle the waters of autumn.

To what shall I turn for solace then, now that my boats I've abandoned?

'Wine banners and fans of the singing girls, these shall welcome me.

Taken from: The Local Cultures of South and East China By Wolfram Eberhard

In Lang-chou (a Pa country) an elephant took a wood gatherer of the Yao tribe into the mountain so the man would cure a sick elephant and in recompense the man received a large tusk which he sold to a foreigner in Hung-chou (North of Canton in which in Tang times many Persians were living) for 400.000 cash.

A woodcutter of the Mo-yao tribe is brought by an elephant into marshlands, where an aged elephant needs him to remove a bamboo splinter from its foot and treat the wound. They give him a large tusk and take him home. He sells the tusk in Hung-chou to an Iranian merchant, but the authorities submit it to Empress Wu. It contains twin dragon-figures, and she gives the first owner an annual pension for life.

T'ai-p'ing Kuang Chi 太平廣記(Book on Magic)

Taken from: The Muslim Merchants of Premodern China by John W. Chaffee,

A Tang tale of one Chen Wuzhen 陳武振, whose mansion in Zhenzhou (modern Yaxian in southwestern Hainan) was filled with gold, rhinoceros horns, elephant’s ivories and hawksbill turtles. The source of this wealth came from merchants from the west whose ships had foundered on the coast. His success in doing so was attributed to his moude fa 牟得法 (method of capture), which involved reciting incantations from a mountain when a merchant ship appeared so as to call up wind and waves and trap the ship on the coast.

Li Fang: Taiping Yulan (Imperial Digest of Taiping) (983)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Taken from: The Siren of Cirebon. A Tenth-Century Trading Vessel Lost in the Java Sea. By Horst Hubertus Liebner.

Christie, Anthony (1957): 'An Obscure Passage from the "Periplus: ΚΟΛΑΝΔΙΟφΩΝΤΑ ΤΑ ΜΕΓΙΣΤΑ"', Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London,19 (2), 345-53

Manguin, Pierre-Yves: (1993b): 'Trading Ships of the South China Sea: Shipbuilding Techniques and Their Role in the History of the Devel-opment of Asian Trade Networks', Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient,36 (3), 253-80.

A quotation from a lost Chinese account of the late third century explains:

Yuan 769

Foreigners call ships bo. The biggest are 20 chang or more in length, and two or three chang above the waterline. Seen from above they resemble covered galleries. They carry six to seven hundred men and a cargo of 10,000 hu.

The men from beyond our frontiers use four sails for their ships, varying with the size of the ships. These sails are connected with each other from bow to stern. [...] The four sails do not face directly forward, but are made to move together to one side or the other with the direction of the breeze. [...] The pressure [of the wind] swells [the sails] from behind and is thrown from one to the other, so that they all profit from its force. If it is violent, they diminish or augment [the surface of the sails] according to conditions. This oblique [rig], which permits the sails to receive from one another the breath of the wind, obviates the anxiety attendant upon having high masts.

These measurements have been understood to ‘indicate a vessel of about 170 feet overall, with a freeboard of some 16 feet or more’ and a carrying capacity of ‘c. 600 tons deadweight’. See also: Note on KUNLUN Empire

Taken from: Sino-Iranica; Chinese contributions to the history of civilization in ancient Iran, with special reference to the history of cultivated plants and products by Berthold Laufer.

T’ao Hun-kin (d536) writes that; the bulk of styrax was imported on foreign ships, with the report that it came from Ta Ts'in (Middle East) (but comes from Somalia).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Note on Kunlun People

------------------------

In the 3rd century ACE, the Chinese historians wrote about the sea-going vessels of the Kunlun (the Malay). The Kunlun were described as short, wooly-haired, dark-skinned people who

were expert sailors. The Kunlun vessels were known as Kunlun-po with the word po being the Kunlun word for ship. The ships of the Kunlun are described as: extending to 200 feet in length

and standing out of the water up to 20 feet. They were said to be able to hold from 600-700 passengers and 10,000 bushels (900 tons) of cargo. Each ship could sport up to four obliquely mounted

sails.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, describes ships from Chryse in the Malay Archipelago known as Kolan-diphonta or 'Kolan-ships'. The 'Kolan' here are probably the Kunlun of the Chinese

annals.

They (and later the Arabs) were most probably the ones providing the Chinese with black slaves.

The oldest mentions of Kunlun people were clearly black people from South East Asia. Later a clear African element comes in; first a doubtful one but later with convincing evidence .

Examples:

Hui-lin in his Ch’ieh Ching Yin I (737-820) when talking about the Kunlun people: There are many races and varieties of them thus there are the Zangis (the single character used to write this is;

seng), the Turmi, the Kurdang and the Khmer.

Tuo Tuo (1238-1298) (Sung Shi) In the second year of Tai-ping Hsing Kuo (AD 977) Arabia sent the ambassador Pu-sze-na, the vice-ambassador Mo-ho-mo (Mahmud), and the judge Pu-lo, with the

products of their country as presents. Their attendants had sunken eyes and black skin and they were called Kun-lun-nu.

Chou Ch'u-fei (1178) Ling-wai-tai-ta has a chapter on; Kouen-Louen ts'eng-k'i(the land of the blacks) which is undoubtedly Madagascar.

At the same time the black people of South East Asia remain Kunlun too.

Slave hunting went on in South East Asia as in Africa: Duarte Barbosa (begin 16th century): Many slaves were shipped from the island of Sunda (between Bali and Timor) to China.

Ge Chengyong 葛承雍. 2006. "Tang chang'an heiren laiyuan xunzong" 唐長安黑人 來源尋踪 [The origin of black people in Chang'an City of the Tang dynasty]. Zhonghua wenshi luncong 中華文史論叢 65: 1–27.

Zhang, Xinglang (1930) in his article: Importation of Negro Slaves to China Under the T'ang Dynasty asserted that the Negro slaves were imported by Muslims from Africa into China.

In 2001, Chinese historian Ge Chengyong criticized Zhang’s view in an article to probe the origin of Black people living in Chang-an city in the Tang Dynasty and drew a conclusion different from Zhang’s. Considering the thesis of the “African origin” not convincing enough, he suggested that the Black people were not Negroid from Africa but Negrito from Nan Hai (south sea, present Southeast Asia and called Kunlun). Some of the Kunlun were part of foreigners’ annual tribute to Chinese authorities, some were left in China by foreign envoys, and some were enslaved people sold to the coastal regions. As for the term Sengzhi, it is generally considered to be identical to Zanj (other forms such as Zinj, Zenj, Zandj, Zanghi) and is a word used by the Arabs to refer to the East African coast. …… Ge did not agree with the view, considering Sengzhi an expression of Buddhism (seng=monk) in Nanhai in early times. It is more proper to look for the origins of Black people in Southeast Asia rather than in Africa (Ge, 2001), a view that is accepted by scholars in China (e.g. Cheng, 2002; Liang, 2004)

Ge Chengyong: Some of my peers and predecessors have thought that these dark-skinned people, with curly hair, broad nose and thick lips, hailed from Africa. I believe they are more likely to have come from Southeast Asia, for example the Indonesian archipelago.

Between the fourth and sixth centuries, to which the pottery figurine (of black people=Kunlun found in China) has been traced, the trade route between China and Africa merely connected the Chinese empire with Egypt. So there is a very slim possibility that these men came from the heart of the African continent. On the other hand, words about them, albeit scant, appeared in writings of the time in which they are portrayed as 'wearing shorts and being superb divers or fast mast-climbers'. These are the traits associated with islanders from Southeast Asia."

Some of these men may have been purchased - or captured - by local tribal leaders or human traders in one of those Indian Ocean islands. From there they could have traveled to what today is Vietnam before moving further toward the heartland of the Chinese empire. Their existence in Tang China has cast a tantalizing beam of light on the society of their adopted home, although most details of that existence are likely to remain forever shrouded in mystery.

The Kunlun slaves, with other non-Chinese domestic servants, were so popular at the time that having them within the household became not only fashionable but de rigueur for the rich. It was a fashion and a fad that reflected a general fascination with things exotic, a fascination that gripped all of society.

Note: with this last phrase he is referring to: Yeh Tzu-Ch'i: Ts'ao-mu-tzu (1378) (The Book of the Fading-like-Grass Master): With the northerners (men living in the North), maid servants were without fail Kao-li girls, man-servants were Negroes. Otherwise, they were said not to be perfect gentlemen.

African diaspora in China by Li Anshuan p465

Black-skinned people are a large group who settled in various places in the world. There is no reason to assume that the Black people in China had only one origin. When Arabia sent a delegation headed by its ambassador to China in 977 CE, “their attendants had sunken eyes and Black skin and they were called Kunlun nu”, according to the History of the Song Dynasty. They could have been from Africa. As for those of Indian origin, there were two groups. One is known as the “untouchables”, who as the indigenous inhabitants contributed a great deal to the civilisation of the Indus River Valley. The other group comprises those who migrated to India or were brought by Arabs or Indians from East Africa as slaves (Rashidi & Sertima 2007: 65—120). The third origin is Southeast Asia, which many works have mentioned, Ge Chengyong being representative of this view (Ge Chengyong 2001).

Regarding the origin of the Black people in the Tang period, Zhang Xinglang points to Africa and Ge Chengyong suggests Southeast Asia, a kind of “singular origin”. After examining both arguments, although based on rich material and sound logic, it is clear that each emphasises the positive evidence while neglecting materials contrary to their view. Historical research should be more careful and open the door for alternative explanations. In sum, multiple origins might be a more reasonable and convincing answer to the question.

Early Global Interconnectivity across the Indian Ocean Angela Schottenhammer · 2019

(About the Senqi slaves brought to China)

We confront the fundamental question of whether these individuals with origins unspecified by the sources were in fact even actually African. At least initially, having only exceedingly rare and incidental contact with them, the Chinese applied the terms sengzhi and cengqi not to Africans at all but instead to the welter of Indonesian archipelago tribal peoples with whom they had for centuries much more commonly and frequently interacted. We can certainly assume such to have been the case from the inception of the use of such terms through the duration of the Tang dynasty. Indeed, entertaining the prospect that neither the enslaved children from Java nor the enslaved maiden from Srivijaya were necessarily African, the late sinologist Edward Schafer (1913-1991) speculated that these human offerings to the Chinese court at Chang’an may well have been of Malay-Negrito stock. Indeed, even as early as Tang times, the Chinese were evidently aware of an island northwest of Eastern Sumatra or Palembang (=Foshiguo) that was called Gegesengqiguo (Schafer’s Kat-kat Zangi Country), whose inhabitants are described as: prone to violence and who, once they have boarded their boats, are much to be feared.

Li, J. 1982.“Examination of Kunlun Slaves in the Tang Dynasty.”Wenshi 6: 98–118.

Li Jiping 李季平. 1982. "Tangdai kunlunnukao" 唐代崑崙奴考 [A study of Kunlun slaves in the Tang dynasty]. Wenshi 文史 16: 292–98.

"Some of my peers and predecessors have thought that these dark-skinned people, with curly hair, broad nose and thick lips, hailed from Africa. I believe they are more likely to have come from Southeast Asia, for example the Indonesian archipelago.

"Between the fourth and sixth centuries, to which the pottery figurine has been traced, the trade route between China and Africa merely connected the Chinese empire with Egypt. So there is a very slim possibility that these men came from the heart of the African continent. On the other hand, words about them, albeit scant, appeared in writings of the time in which they are portrayed as 'wearing shorts and being superb divers or fast mast-climbers'. These are the traits associated with islanders from Southeast Asia."

"Some of these men may have been purchased - or captured - by local tribal leaders or human traders in one of those Indian Ocean islands," Ge says. "From there they could have traveled to what today is Vietnam before moving further toward the heartland of the Chinese empire. Their existence in Tang China has cast a tantalizing beam of light on the society of their adopted home, although most details of that existence are likely to remain forever shrouded in mystery."

Ge Chengyong says that the Kunlun slaves, with other non-Chinese domestic servants, were so popular at the time that having them within the household became not only fashionable but de rigueur for the rich.

Note: with this last phrase he is referring to: Yeh Tzu-Ch'i: Ts'ao-mu-tzu (1378) (The Book of the Fading-like-Grass Master): With the northerners (men living in the North), maid servants were without fail Kao-li girls, man-servants were Negroes. Otherwise, they were said not to be perfect gentlemen.

"It was a fashion and a fad that reflected a general fascination with things exotic, a fascination that gripped all of society."

Taken from: Liang J. (2004) Some Thoughts about the Source of Kunlun Slaves in Tang Dynasty. P58-62.

There are roughly the following views and opinions:

(1) From North Africa. In Chang'an of the Tang Dynasty, "there were expatriates from more than forty countries in the East and the West, including blacks (Kunlun slaves) from Africa."

(2) Southeast Asia. Ge Chengyong pointed out that the source of blacks in the Tang Dynasty was not Africa but Southeast Asia, that is, the Negrito people. Han Zhenhua pointed out that Kunlun slaves refer to the small black people on the Indochinese Peninsula, including the Ka people in Laos. The Kunlun people originally referred to the aboriginal people of the Indochina peninsula. All the countries that ruled these small black people on the peninsula were called "Kunlun and the like" in Chinese records.

(3) India. In Tan Sitong's "Poems on Lifting the Wall in Prison", there is "I smile to the sky with my sword across my face, and go to Kunlun. " He believes that the Kunlun slaves should refer to the Indians: Zou Chenfan wrote the journey of the Western Expedition, saying that Mount Himalaya is Kunlun, which is accurate and credible. Mount Himalaya is in northern India. The Tang Dynasty called Indians: Kunlun, which is also true.

(4) The aborigines of Kunlun in western China. Some people in modern times simply regard "Kunlun" as the Kunlun Mountains located in Northwest China today, so they believe that the Kunlun slaves are the aborigines of the present Kunlun Mountains, who were brought into China from the Western Regions through the Northwest Silk Trade. Among these scholars, quite a few believe that the Kunlun slaves were brought by Arab merchants from north-eastern Africa to enter China via India or directly enter southern China by sea. There are generally two reasons: First, the biggest feature of Kunlun slaves is their dark, so the first thing people think of is Africans. Second, Arab businessmen at that time often traveled between and entered China to do business, and there are indeed records in Chinese historical records of Arab businessmen selling slaves and black African countries. For example, in "Huichao Going to the Five Tianzhu Biography Persian Kingdom", it is said that Persians often go to the Lion Kingdom (that is, Ceylon) to get treasures, and to Kunlun Kingdom to get gold. The Kunlun Kingdom is said to be the land of African blacks, because the gold produced in Africa has been famous all over the world since ancient times. Zhou Qufei's "Lingwaidaida" Volume 3 " Kunlun-ceng-qi (Madagascar)" says: "There are many savages on the island, their bodies are like black paint, and their fists are drawn. They are lured to capture them with food and sell them as slaves." Zhao Rushi " The article "Miscellaneous Countries on the Sea" in the volume of "Zhu Fan Zhi" also says: " Kunlun-ceng-qi (Madagascar) is in the southwest sea, connecting large islands. There are often rocs flying, covering the sun and moving the sundial. There are camels, and rocs will swallow them when they meet. "

(5) Dwarf black Kunlun slaves from the South China Sea Dwarf black.

According to modern textual research, the main source of " Kunlun slaves was Asian Malay blacks from Saigon (Kunlun Island in the outer sea (today)). According to Indian historical records, Saigon has been the largest slave market in Asia since the third century AD, mainly selling slaves to China, and this slave trade continued until the Ming Dynasty. However, the ancients had inaccurate and mistakenly pronounced "Chai stick" as "Kunlun", which is how they got the name "Kunlun slave".

(6) From the point of view of clothing, most of the black figurines unearthed later are also naked upper body oblique silk belt, banner around the waist or wearing shorts. This is very consistent with the image of the Kunlun people "Barefoot Ganman" recorded in "Nanhai Jigui Neifa Biography" by Yijing, an eminent monk in the Tang Dynasty. "Ganman" is Sanskrit, referring to the underwear worn by the lower body. A very obvious feature that has nothing to do with ancient African black clothing. Ge Chengyong said that many authoritative scholars believed that blacks in the Tang Dynasty came from Africa.

The stream of black-slaves out of South-East Asia to China.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Li Yansho: Nan-shi 南史 (History of the Southern Dynasties), (659)

Sources from the fourth and fifth centuries use the term kunlun to describe people with dark skin. An anecdote from a history of the Liu Song dynasty (420-479), for example, describes an emperor who had a kunlun slave, marking the earliest mention of a kunlun person rather than the term's use as an adjective for a dark-skinned. Chinese person. This kunlun slave, Bai Zhu, was "often at [the emperor's] side. He was ordered to beat the ministers and officials with a stick," and even the highest-ranking ministers "feared his venom."

Liu Xu: (940) Jiu Tang Shu (Old History of the Tang Dynasty)

Yuan4, f1v

In 684 a Kunlun of Kouang - tcheou (Guangzhou) killed the tou-tou Lou Yuan-jouei.

This appears to be the first mention of a community of kunlun living in China, but not a slave community.

Zhang Ji (8th century Tang poet): Kunlun-er (Kunlun-kids)

These children the poem says sailed from an island in the sea on their way to China (Han lands)(2) a barbarian guest (manke)(1) (obviously a foreign merchant) had bought them in Yulinzhou. (=close to the Vietnamese Chinese border.)(3)

Home to the Kunlun is the islands amidst the Southern Sea;

Yet, led forth by Man (1) visitors, they have come to roam Han (2) lands.

Parrots and cockatoos must have taught them speech,

As, riding upon billowing waves, they first entered through the Region of Teeming Forests. (3)

Gold rings once dangled luridly from their ears;

Which conch-spiraled hair, long and coiling, they still refuse to bind their heads.

Black as lacquer is their flesh and skin received from nature;

Half-stripped of tree-floss garments, they stride about with bodies exposed.

Chu Yu : P'ing-chou k'ot'an (1119) (Pinzhou Chats)

Yuan 2 §8

Most of the wealthy in Kuang-chou (Canton) possessed kuei nu (devil or negro slaves). They are very strong, able to carry weights of several hundred catties (one catty 750gr). Their speech and their desires are unintelligible... Their nature is simple and they do not run away. They are called wild men. Their color is black as ink, their lips are red and their teeth white, their hair is curly and yellow (huang). There are males and females.... (Their sexes are classified to denote the male and female of animals and some birds). They live in the mountains (or islands) beyond the sea. They eat raw things. If, in captivity, they are given cooked food, in a few days they get diarrhea.... (diarrhea is called changing the bowls "huanchang"). This makes some of them fall ill and die. If they do not die one can keep them. After they have been domesticated for a long time they are able to understand human speech, but they can not utter it themselves. There is also a kind of offshore savage, who does not lives into the water, which is called Kunlun slave.

The yellow hair shows we have here people from the Solomon Islands.

Houang Cheng-ts'eng : Si Yang tchao kong tien lou (Records on tributes made by foreign countries from the Western Ocean) (1520)

The Country of Java

In 1381 the king (of java) sent an address written on leaves of gold, together with tribute, and also 300 black slaves.

Zhang, Tingyu: Ming Shi (Records of the Ming Dynasty) (1739)

(Yuan 324)

In the year 1381 they (Java) sent envoys, who brought as tribute 300 black slaves (Gonghei nu) and products of the country. The next year they brought again black slaves, men and women, to the number of a hundred, eight large pearls and 75,000 catties of pepper.