Bimaruh / Layrana (Vohemar) or (Bemanevika ???)

--------------------------------------------------------------

Ibn Said (1250) and Abulfeda (d1331) mention it as Layrana.

Ibn Majid (1470) is the only author who mentions this place as Bimaruh.

Note: He gives at 9 fingers of Nach: Bandar Darwis at 12.4°S; Anamil at 15.8°S; Manzalagi at 15.2°S and Bimaruh at 13.3°S so we can see how problematic the description ‘at 9 fingers’ is.

However, the location at 13.3°S fits way better for Bandar Bani Ismail while another medieval harbor Bemanevika at 14.1°S at the mouth of the Bemarivo river fits better for Bimaruh. However only Ibrahim Khoury agrees with this. All other authors make Bimaruh = Vohemar. (see next paragraphs).

Vohemar

Taken from: Taken from: Madagascar, Comores et Mascareignes à travers la Hawiya d'Ibn Magid (866 H. /1462). Par François VIRE et Jean-Claude HEBERT.

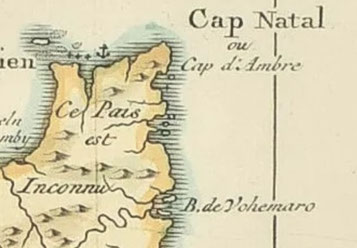

Can also be read Bimaruwa or Bimariwuh. We note, through the portulans, the forms Bemaro, Bamaro, Boamaro, Bimaro, Bonamare, Demaro, Demoro, Maaro, to end up with Vohemaro (see Kammerer, op. cit., 66).

The nine fingers in height of Big Bear carry Vohemar a little too far to the south and would correspond to the mouth of the Bemarivo river (= "very shallow"), a name which is strikingly similar to the Arabized toponym; but the name “Bemarivo” is frequent in the north of Madagascar, both in the west and in the east, and could not prevail over Vohemar for the location of Bimarth which was the seat of the reigning authority of the time (baldat al-sultan).

Note: Except of listing Bimaruh at 9 fingers of Nach, Ibn Majid also in a different chapter writes: ‘There is however, at its extreme North end with its harbors, the residence of the Sultan’. This is supposed to also be a reference to put Bimaruh more to the north.

Taken from: La longue histoire de Vohemar - 1ère partie: Les Rasikajy Écrit par Suzanne Reutt

The Portuguese Diogo de Couto, evoking the exploration of Lobo de Sousa in 1557 writes: "The Moors of the coast of Malindi who come from ancient times to Madagascar, founded two cities there, where their descendants still live under the authority of sheiks; one is in an island located in the middle of a bay called Manzalage which we will talk about shortly, and the other on the northeast coast in another bay called Bimaro” (Vohemar).

Taken from: The History of Civilisation in North Madagascar; Pierre Vérin

De Barros (1628:III-I-2) in Da Asia Portugueza : Pedreanes (commander of the Santo Antonio) had discovered a port (in 1515) called Bemaro ( Vohemar ) by the natives and had bought a great deal of amber there.

Taken from: La cartographie de Madagascar by Gravier, Gabriel 1896

Vohemar who was named:

-Maharo in the map of Henri II, 1546

-Boamaro by Gysbert, 1599

-Amarago, by Cauche, 1651

-Boamarage by Sanson, 1655

-Vohemaro, by Flacourt, 1656

-Veimart by Le Gentil, 1769.

Taken from: The archaeological site at Vohemar in a regional geographical and geological context; Guido Schreurs et Jean-Aimé Rakotoarisoa.

Although widespread excavations have been carried out at Vohemar, the site of the settlement that most likely existed close to the necropolis has not been discovered. Presently, ships enter the harbour of Vohemar from the Indian Ocean through a passageway that is c. 250 m wide. Immediately north of this passageway, there is a large intertidal zone, partially covered with sand and extending for nearly 14 km. Maps of the 16th and 17th centuries show three fair-sized islands just north of the town of Vohemar (e.g. Flacourt 1661, Coronelli 1690). It is possible that the intertidal zone north of Vohemar once represented several larger islands, of which only the Ilots Noirs and Ile Verte remain today.

The Frenchman Mayeur travelled extensively on foot in northern Madagascar and also visited Vohemar. He has the following entry for May 1775:

Just before arriving south of Vohemar, one can see the remains of two stone buildings of a square shape, which seem to be old . . . It is customary [among the people of this region] to say that they were built by white men who inhabited this part of the island in remote times. At that time, there was a point of land which extended far off the coast and formed a fine, wide, safe harbor . . . but one day a strong hurricane submerged the point, and the harbor was destroyed and silted; after this disaster, the settlement was abandoned and the white men left. (Corby and Mayeur 2011: 19)

Taken from: Les apports culturels et la contribution africaine au peuplement de Madagascar, par Pierre Vérin.

In 1941-1942, excavations carried out in the necropolis of Vohemar, in the northeast of the island, revealed to the world the existence of the Rasikajy civilization. We have since known that the installation in this region of a commercial city participated in the expansion of the Islamized in the north of Madagascar and that it was founded in the 14th century to disappear in the 18th century.

Taken from : Madagascar: The Development of Trading Ports and the Interior; Beaujard, Philippe.

Along the northeastern coast, the main trading ports were Vohemar, which developed around the thirteenth century, and Bemanevika, located south of Vohemar (Vérin 1975a). Recent research conducted at Vohemar has yielded a dating from the ninth century (Radimilahy, p.c.). The rise of Vohemar from the thirteenth century onward is likely to have been linked to new Austronesian migrations. Chinese pottery found in the tombs is usually dated later than the fourteenth century; a few pieces, however, go back to the thirteenth century; this matches a dating obtained in the most ancient part of the cemetery by Vernier and Millot (1971). The abundance of Chinese ceramics, the presence of other objects from eastern Asia or Southeast Asia, and the extent of the grave’s contents – unlike northwestern Malagasy assemblages – all reveal likely relations between Vohemar and both South Asia and Southeast Asia. This hypothesis agrees with what we understand of the Austronesian arrivals from Sumatra and Java between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. While one cannot determine the extent of the Islamic presence at Irodo, the skeletons in the cemetery at Vohemar were found lying in positions complying with Muslim practices. This said, depositing objects in tombs is not an Islamic custom, as McBain correctly points out (1992: 71).

Chlorite schist stone vessels were a significant part of the discoveries in Vohemar, and control over this stonework must have been one of the sources of wealth for this city. Stone vessels were luxury goods, and were hoarded; they may have played the same role of “currency” as did Chinese ceramics, which were present on a large scale from the fifteenth century onward. Such vessels and other stone items were exported to the Comoros and East Africa between the ninth and fifteenth centuries. Malagasy trading ports maintained privileged relationships with some African towns: while a great deal of chlorite schist (probably originating in Madagascar) has been recovered at Manda and Pemba, few chlorite-schist vessels and fragments have been unearthed at Shanga.

The civilization of northeastern Madagascar used chlorite schist to produce not only stone vessels, but also bowls, lamps, incense-burners, troughs, and nozzles for wells.

Other sites of settlements located mostly near the mouths of rivers, and often near quarries of chlorite schist, have been discovered south of Vohemar. Two of these are Mahanara and Bemanevika, at the mouth of the Bemarivo River; they have yielded shards of yellow and green sgraffiato with a red paste that is not unlike the sgraffiato found at Mahilaka (thirteenth century).

Ibn Sa‘id (thirteenth century), referring to a text by Ibn Fatima (now lost), wrote: Among the towns of the island of Qumr, . . . which is said to be four months walk long and a twenty days walk along its largest width, one finds Layrana . . . Like Mogadisho, [Layrana] belongs to Muslims. Its inhabitants are a mixture of men from all countries. It is a town where ships come and go. The Saykhs who exercise authority there try to remain on good terms with the prince of the city of Malay, which is situated further east. Layrana is located at 102° – minus a few minutes – of longitude and 0°324 of southern latitude, on a large estuary to the west of the city.

Layrana, also mentioned by Abu’l-Fida (around 1320), may have been either Mahilaka or Vohemar. Shepherd (1982) links Layrana to Iharana, the former name of Vohemar.

The excavations conducted in the cemetery of Vohemar from 1941 onward are famous due to the wealth of the discoveries made there and to the total absence of scientific rigor of these excavations. The tombs, some bordered by carved coral slabs, yielded skeletons and abundant funerary assemblages. Two-thirds of the 246 tombs excavated in 1941 and half of the 310 tombs opened in 1942 contained burial offerings.

It would be boring [sic] to describe all the tombs,” write Gaudebout and Vernier (1941b: 103). They provide us only with the following “synthesis”:

The tombs [containing archaeological material] have yielded a total of about 800 objects; while some tombs contained only three or four artefacts, others contained as many as a dozen or more. The richest tombs were located in the eastern part of the clusters; they were obviously linked to the ruling families. Thus, one could have the luck to find beside the skull an iron stylus pointing to the east; on the forehead or the occiput, a Chinese bowl and red glass beads; the remnants of

an embroidered cap covering the top of the head; before the face, a bronze mirror, a copper needle and a kohl phial (in a female’s tomb); under the chin or behind the neck, a spoon made from shell; around the neck, agate or rock crystal beads; before the chest, a Chinese plate; against the chest or along the thighbone (in a man’s tomb) a saber or a machete, tip pointing eastward; along the humerus, an iron knife; copper or silver bracelets on wrists; various rings on fingers; chains on ankles, and, lastly, near the feet, a chlorite-schist vessel, usually upside down, with or without lid, or a footed cup of the same substance: note that this type of cup was always found in a level higher than that of other objects. (Vernier and Millot 1971: 19)

A large plate (sometimes Chinese celadon ware) was often vertically planted to the east of the skulls. Chinese or Islamic bowls were placed on the foreheads of the deceased (Vérin 1986: 221). An incense burner was probably left above the tomb.

The Chinese pottery excavated is dated to the period between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries: it includes “brown monochrome” (dated to the Song period), “white monochrome” (Song or Ming), celadons (some showing a “head-to-tail” fish motif, dated to the thirteenth or fourteenth century), and blue-and-white porcelain. While the oldest blue-and-white porcelain vessel is a small cup dated to the fourteenth century, most of these objects date to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (McBain 1992) and some to the seventeenth century (see Zhao 2014: 98). The gourd shaped ceramics found, as well as the celadons, may date as far back as the early fourteenth century (Schreurs et al. 2011: 115). Some pieces may be imitations of Chinese pottery, but are of Islamic or southeast Asian origin. Using the reports added to the 1941 “Notes,” it remains impossible to estimate quantities of Chinese pottery as compared to Islamic ware (Verin 1975a: 773). Among the latter, Verin signals dishes, white-cream bowls “with ears,” and “large bowls with a red paste, decorated with arabesques.” One dish excavated is believed to bear an inscription in an Indian language, and a small bowl dated to the fifteenth century is “decorated with bands showing Sanskrit characters” (Verin 1975a: 804–805). The availability of blue-and-white porcelain reveals Vohemar’s level of wealth, although the plates excavated are generally small and relatively coarse. The artisanal workshops of southern China, and Indochina, produced coarser ceramic ware for export.

Two gold coins have been unearthed: one imitates an Abbasid dinar, and the other a Fatimid dinar from Egypt. One of these coins was found “in the mouth of a Skeleton,” while the other was “attached by a chain to the forehead of a Skeleton” (Gaudebout and Vernier 1941b: 110; Verin 1986: 251). Among the jewelry unearthed at Vohemar, Gaudebout signals “two small gold medals, one with Arabic signs translated as ‘Year 515 Sheikh Salim ben Radjab’ [1121], and the other bearing characters [that he] could not decipher”; in addition, one silver ring bore “half-obliterated Chinese characters on the bezel.”

The rock crystal is often portrayed as coming from Vohemar or Nosy Be, but these were merely the loading ports and not the location of the mines (Lacroix 1923, 109–110). Vohemar is important because it was one of the main sites for steatite vase production and because rock crystal was extracted from its hinterland.

Red dots are rock crystal mines.

About 100 iron smelting slag heaps were located in the coastal area between Vohemar and Antalaha and were active from the eleventh to fourteenth centuries AD. About 30 quarries for the production of carved stone vases were located in the hinterland, sometimes quite far from the coast.

Taken from: The Rasikajy civilization in northeast Madagascar: a pre-European Chinese community? By Guido Schreurs, Sandra J.T.M. Evers, Chantal Radimilahy et Jean-Aimé Rakotoarisoa. Études océan Indien 46-47 (2011)

Most evidence for the Rasikajy civilization comes from excavations at a cemetery discovered at the coastal town of Vohemar in northeastern Madagascar (Grandidier 1908). The position of the dead in the tombs at the cemetery of Vohemar has been used to suggest that the civilization had Muslim roots and the presence of imported pottery to indicate engagement in the Indian Ocean maritime trade (Dewar & Wright 1993). Vernier & Millot (1971) consider that most imported pottery found in the tombs dates from between the 14th and 16th CE. (A 14C date on bones from a skeleton excavated at Vohemar revealed an age of 760 ± 60 a (Vernier & Millot 1971), i.e. around 1200 CE.)

Burial objects recovered from the tombs at Vohemar include soapstone objects such as tripod vessels, cups and pierced circular disks; iron objects such as knives, machetes and a saw; jewellery such as silver, bronze and golden rings, bracelets and necklaces; pottery such as dishes, bowls and jars; spoons made from shells, bronze mirrors and needles; glass ware such as flasks in different sizes; beads; decorated bone objects. Most of the pottery found at Vohemar is clearly of Chinese origin and remarkably diverse (Vernier & Millot 1971).

A small, brown stoneware dish from Vohemar shows a raised twin-fish motif in the centre of the interior with the fish swimming in opposite directions (Vernier & Millot 1971:89). Celadon and stoneware dishes with identical motifs have also been found at the Santa Ana gravesite in the Philippines (Locsin & Locsin 1967:73, fig. 53), at kilns in the Longquan region in the province of Zhejiang in SE-China (Hughes-Stanton & Kerr 1982) and in cargoes from shipwrecks, such as the one dated at c. 1323 and found at Sinan, off the coast of South-Korea.

Two white double-gourd pouring vessels spotted with dark markings have been found at Vohemar (Vérin & Millot 1971:128, fig. 137). Similar wares have been uncovered from the gravesite at Santa Ana (Philippines; Locsin & Locsin 1967:95, fig. 77; 97, fig. 79) and from a shipwreck at Pandanan (Philippines) carrying Chinese coins of c. 1430 (Diem 1997; 1998-2001).

Some of the white and blue-and-white porcelain bowls and plates from Vohemar carry Chinese inscriptions at their base that translate in “made under the great Ming dynasty” (Vernier & Millot 1971). The colour, shape and motifs of the blue-and-white bowls and plates from Vohemar suggest that most of the ware has been produced during the Yuan (1279-1368) and/or early Ming (1368-1425) dynasty. However, blue-and-white ware from later periods has also been excavated at Vohemar, notably a large blue-and-white bowl, which carries the inscription: “Great Ming Dynasty, Jiajing (‘Kia-tsing’) period”, i.e. 1521-1567 (Vernier & Millot 1971:111, fig. 117, 118).

Soapstone burial objects at Vohemar

A large number of objects carved from soapstone were found in the tombs at Vohemar (Vernier & Millot 1971, Vérin 1986). Mouren & Rouaix (1913) show that these and other soapstone objects found at other sites along the northeast coast were locally produced. The many excavated tripod vessels show a remarkable resemblance to similar vessels found in ancient graves in China. Other soapstone objects found in the tombs at Vohemar include cups, pearls, pierced circular disks, flat-bottomed dishes, lamps, spindle whorls, a jar, and a turned bowl and pot (Vernier & Millot 1971; Vérin 1972, 1986).

Soapstone objects from other sites

About 750 km south of Vohemar, a soapstone sculpture of an animal is present in the village of Amobhitsara (Vohitsara)(e.g. Jully 1898, A. Grandidier & G. Grandidier 1908, Griffin 2009). The Malagasy refer to the statue as vatolambo (stone wild boar) or vatomasina (sacred stone). The sculpture measures 106 cm in height, and is largely hollow. (Louis Mollet stated that it is the extinct dwarf hippo from Madagascar of which the remains were found close to Antsirabe.

Trade with soapstone objects

An example is a pear-shaped weight (tronc de cone) with an Arabic inscription (in Vernier & Millot 1971) at Mahilaka, a trading port on the northwest coast since the end of the first millennium (Radimilahy 1998). There is also evidence for export of soapstone objects to the Comores (basin at Siwa; Barraux 1959) and Tanzania (tripod vessels in Kilwa; Chittick 1966a, 1966b). The presence of soapstone objects in Comores, Somalia and Tanzania suggests that the Rasikajy participated in the Indian Ocean trade network.

Bemanevika

Because the Portuguese know Vohemar as Bemaro, Bamaro, Boamaro, Bimaro, Bonamare which is close to Bimaruh the site of Bemanevika has little chance to be the Bimaruh of Ibn Majid.

Taken from: Madagascar: The Eighth Continent: Life, Death and Discovery in a Lost World; By Peter Tyson.

Bemanevika, at roughly 25 acres, is one of the largest archeological sites in the region. It is situated at the mouth of the Bemarivo river at 14.1°S. It is also among the earliest site on record for the northeast coast. Verin dates it to the eleventh century, based on a single piece of Islamic sgraffito pottery, a yellow-and-green sherd with a red glaze that he found in the deepest level of one of the five test pits he dug. He also revealed a heap of iron slag, indicating that Bemanevika was an iron-making center, and a well shaft three feet in diameter carved out of chlorite-schist. (“The place is holy, and coins are left there,” Vérin wrote of the well.) Another chlorite-schist well-shaft was discovered at close by Mahanara (ten km to the north at the mouth of the Mahanara river).

Bemanevika is also interesting for its links to Mahilaka, Madagascar’s first city. In their test pits at Bemanevika, Verin and Ramilisonina unearthed pottery just like that found on the other side of the island at Mahilaka, including, besides the sgraffito, imported celadon (a green-brown ceramic of Islamic origin) and thick-rimmed local ware.

Taken from: The History of Civilisation in North Madagascar; Pierre Vérin · 1986

Very little imported pottery has been found at Bemanevika - only five fragments. They are, however, sufficiently well marked, being fifteenth century celadon, 25 cm deep and yellow and green sgraffiato work with a red glaze like that found at the lower levels at Mahilaka. There is soapstone at both levels, but more at the deeper level. Among the chloriteschist objects found are some fragments of lids and vessels, frequently recut, and fishing weights, one of which is pear - shaped. There must also have been other sites in the neighbourhood of Bemanevika. A little to the north - west of the modern village there are stones at ground level, defining an area of 3.70 by 4.00 m which may have been a tomb. The stones must have been taken from quarries.