Sofala

-------

Most of the early authors during the Middle Ages wrote about the land of Sofala. Only much later a certain place was called Sofala or Sufala or Cefala …..(Except for the Persian Hudud al Alam (982) where Sofala is the seat of the Zang King.)

The first three authors are:

-Yahya ibn Barmak; Kitab al- Majisti (The greatest book) (about 800) (Almagest, translated from Ptolemy).

-From Jahiz's Kitab al-Hayawan (Book on Animals) from Basra (869).

-Al-Mas'udi (916) Muruj al-Dhahab wa-Manadin al-Jawhar (Meadows of gold and mines of gems).

Note also: In the Kitab Ghara'ib al-funun wa-mulah al-'uyun (1050) a place is mentioned: ‘the bay of the amir’ this according to Horton, M. (2018) in ‘The Swahili Corridor Revisited’ may be Sofala bay.

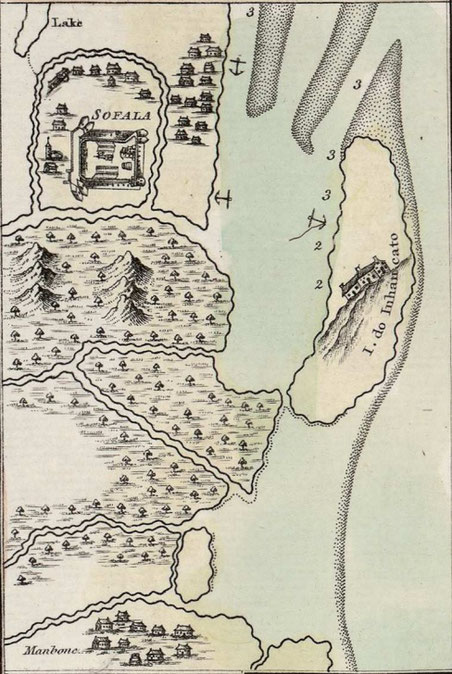

Right: Sofala from Francois de Belleforest 1575.

Taken from: Africa Pilot: South and east coasts of Africa from Cape of Good Hope to Ras Hafun

United States. Hydrographic Office 1916.

Sofala river, is 1.75 miles in width at its entrance, but this width is nearly filled by sand banks drying at low water. Ilha Inhancata, forming the south side of the entrance, and separated from the mainland by a boat channel, is nearly 2 miles in length in the north and south direction, while the northern point of entrance has on it the town and dilapidated fort of Sofala.

The town of Sofala, standing on the sandy peninsula on the northern side of the river entrance, has an estimated population of about 2000, and is the residence of a Portuguese governor; the fort build in 1505, was the first constructed by the Portuguese on the east Coast of Africa. The trade is insignificant, a small quantity of ivory, beeswax, and groundnuts being exported to Beira.

From Sofala river the coast trends in a northerly direction for nearly 20 miles, to the entrance of the Buzi river.

Ibn Majid says: until arriving, o accompanying, to the eminent Sulan (or Sulanyat), that is a reef above Sofala. And everything here is sand, my pilot!

Taken from: THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE SOFALA COAST by R. W. DICKINSON 1975

Before the caravels arrived, the gold traffic from the Karanga deposits inland was controlled at the coast by a group of Muslim traders ruled by Sheikh Yusuf, who had just declared his independence from his traditional suzerain in Kilwa. The Sofalan communities are described in contemporary

Portuguese documents. All the folk were black, but two different societies lived side by side. Yusuf's Traders numbered around 800 (Alcagova 1506: 396). They were 'Moors' or Muslims, and dressed quite differently from the 'Caffres', or tribesmen, who lived in their thousands around the Muslim settlement. Muslims wore turbans, sashes, and silk or cotton robes, carried scimitars with gold-decorated ivory handles in their belts, and sat in council on three-legged stools with kaross-covered seats (Gois 1566). The local tribesmen who attacked the fort in 1506 under their leader, Moconde, were naked, fought with assegais, clubs, bows and arrows, including incendiary arrows (Castanheda 1551). They wore cotton garments, and their women loaded their legs with copper bangles and pierced their lips (Figueroa 1505-1511: 599). Fat-tailed sheep, cattle and poultry were kept at Sofala; rice, sugar-cane, coconuts, and millet, from which sadza was made, were the staple foodstuffs (Figueroa 1505-1511:595 & 599). Fish, oddly enough, is not mentioned in the earliest accounts, but later sixteenth-century writers repair this omission.

In one respect, Muslims and tribesmen were alike: both lived in thatched pole and daga huts (Barros 1552). The sheikh's house was long and narrow, capable of seating a hundred men, with a small audience apartment at the end (Castanheda 1551).

Yusuf's settlement lay half a league (between 2 and 3 km) from the village which stood just seaward of the fort. The fort, originally a log palisade, was later replaced in stone (Pereira 1507: 47; Almada 1516: 281). The present coast at this point has lost a strip of land up to half a kilometre wide by sea encroachment since Captain Owen published his survey (Owen 1833).

The Tomb at the extreme north-west, according to oral tradition (Dickinson 1968:46), contains the body of a Shafi saint who arrived in Sofala before the Portuguese. From the name which some give to the person buried there, it might be the grave of Sheikh Yusuf, killed by the Portuguese after the siege. The structures in the little cemetery have no inscriptions, and are no more than forty years old (Earthy 1931: 224), but the tradition is ancient. The area close to the Tomb fits well the location of Sheikh Yusuf's village as described in sixteenth-century accounts.

The brief excavations confirm what may have been suspected from early sixteenth-century documents but could not hitherto be stated positively: that the tribal African folk met by the Portuguese around A.D. 1500 were a branch of the Shona world of the monomotapan hegemony inland. (No settlements older than around AD 1500 were found till now in Sofala). They lived in pole and daga huts, like those of the modern rural Shona. They used iron implements and kept cattle. Meat, fish and shellfish were included in their diet, and spindle-whorls show the manufacture of thread as a local industry. Ornaments of bronze were worn and combs used. Cane-glass-bead patterns were predominantly yellow at Muringare and Indian red at Sofala, with accents of other colors.

Taken from: Archaeological Sites on the Bay of Sofala by Gerhard Liesegang.

Due to the forces of erosion, the Portuguese fortress built at Sofala in the sixteenth century has nearly disappeared. Even less is left of the Portuguese settlement to the north of the fortress founded in the same period. But the existence and nature of this site is well documented through drawings, plans, descriptions, and photographs. The precise location of the pre-Portuguese Islamic settlement, whose age seems to be uncertain, has, however not yet been located.

The Question of the Pre-Portuguese Settlement:

Portuguese sources indicate that the first fortification built in 1505 by Anhaya was not constructed in the centre of an existing settlement, but rather between that of the head of the local Islamic community, "Cufe" [Yusufu], and another village. The former was located "half a league" (2 to 3 km) from the bar and the other near the bar itself (Axelson, pp. 82-3; G6is, II, p. 31; Lobato, 1954). It is likely that the site of the fort remained the same when it was rebuilt in stone.

The outstanding question is whether or not the site inhabited by the Muslims has disappeared. The following 1844 account of the area by an inhabitant of Sofala, Joao Juliao da Silva, raises the possibility that this site has not been washed away: There are three notable rivers of salt water which flow into the bay (from the north). The first is Inhaminagi [Nyaminaji] which is a quarter of a league away from the fortress. According to tradition and our histories the Arab King named Essufo [Yusufu] lived there before the arrival of the Portuguese ...

The "Inhaminagi river" must be the one which is called "Mwenye Mukulu" today. (The two others are the Ndungulu and Nyamakande . According to another manuscript by da Silva written in 1846 there were (unspecified) "vestiges" of the old settlement near the "'Inhaminagi". Today this creek is named after the Islamic saint whose tomb is close to it. Castilho's 1889 account was apparently the first reference to the tomb. The tomb itself must have undergone at least three modifications in the last fifty years. Dickinson collected two oral traditions concerning the name of the man associated with it. The custodian called him Saide Abdul Raman (Sayyid 'Abd aI-Rahman?), while other local inhabitants, whose knowledge may directly or indirectly derive from written sources, call him "Issufo [Yusufu]". This is the name of the head of the Islamic community killed in 1506 by the Portuguese (his name is also mentioned by J. J. da Silva (1844)). The question whether or not this tomb does in fact stand on his grave cannot be answered with the present scant knowledge.

According to the chronicler Gois (1566 II, p. 31), the fort was at a distance of a crossbow shot from the "river" when it was founded. Between it and the bar there was still another village of "400 households (visinhos)". Today the ruins of the fort are partially covered with water when the tide comes in. But there existed a village inhabited by the Muslim population between the fortress and the open sea even in the early nineteenth century.

This map of 1864 shows no more Swahili village only the Portuguese settlement.

The end of the Sofala Fortress

Taken from : Sofala : d’un pôle commercial swahili d’envergure vers un site archéologique identifié ?

Jules Frémeaux 2018

In this article he puts together what exactly Ibn Majid said about Sofala in his Sufaliyya.

Sufala

The Sufaliya does not give us much information about Sofala, as most of the text is about navigation. But the very fact that an entire treatise is dedicated to the routes to Sofala tells us something about its importance:

“If you reach the [Sufala] estuary at night, approach

And lower the sails until morning, you'll find the entrance

Marked on its perimeter by stakes.

The local fishermen will come to you,

You thus enter Sufala and be grateful.”

If Ibn Majid writes this poem, it is because trade flows must be important there and it meets a need. Ibn Majid produces and uses concrete knowledge, the information is always precise and beyond the poetic and religious framework the information of the whole poem does not seek to be symbolic, but practical. In the previous quotation, he tells us that Sofala is indicated by stakes.

“There, the landmarks are made of wooden stakes,

To the estuary, [placed] by someone seeking merits. »

In these two quotations, we are told that wooden stakes indicate the way. This device allows boats not to approach shoals and to indicate navigable channels. Ibn Majid gives descriptions for docking in many other commercial places and no other seems to have this kind of facility. This information could let us think that the port of Sofala is more organized than the average. In addition, the author often tells us that Sofala is clearly visible. For other cities, it indicates small landmarks to find your bearings. For Sofala, there does not seem to be a problem:

“And hasten to the entrance with the [customary] festivities

And go to the city near the entrance,

You will see it clearly. »

Politically, Ibn Majid gives us two seemingly contradictory informations.

“But Sufala is in Munamunawa

And the name of the king's seat is Zimbawa"

A little further on, he tells us:

“But Sufala, the port of gold,

Is under the domination of Kilwa, do not argue!

I mean the coast, O you who question me! »

Ibn Majid tells us that Sofala is under the domination of the Monomotapa Empire and the Sultanate of Kilwa. It is well integrated into the sphere of influence of Kilwa in the 12th century by Sultan Suleiman Hassan. But Sofala in fact keeps its autonomy and constitutes as the interface between the empire of Monomotapa and Kilwa. At the end of the 15th century, Sofala would have broken its ties with Kilwa on the occasion of a succession of the sultanate. Thus this inconsistency could be linked to an addition to the original copy linked to the new situation of Sofala. It is more likely, however, that the two quotes are not contradictory in the author's pen and that Sofala is indeed considered to be under the influence of both entities. Ibn Majid insists on the commercial interest of Sofala. As we can see in the previous quote, Sofala is often referred to as the port of gold, the provenance of which it even tells us.

[But] the gold mines, note my indication,

Over Sufala and the coast, oh my brother, to those mines,

The path is more than a month, know that well!

This statement is difficult to interpret. Arab merchants can easily have this information in Sofala, but without necessarily understanding where this place is located a month's walk away. It could be the plateau of Zimbabwe or Nubia. As we saw above, the distorted view of Africa leads them to believe that the Zimbabwe plateau and Nubia are neighbors:

“[Live] at the Kwama estuary, I have it from information.

This estuary [penetrates] far [inland] and its origin

Is in the land of the Nile of Egypt, where it separates.

The inhabitants [of the country] between Sufala

And Kajalwa are evil infidels;

They are called Muna, from the name of a great king,

Muna Batur, and what an infidel he is!

He has a mine like that of as-Sufal

Because his country immediately follows him in the East.

From the east of Sufala you can see

The kingdom of the infidels, upon it be aversion!

It reigns from the "Estuaries" to Zanzibar

On land and sea, as he wills,

And he owns gold mines,

For they are in the land of the infidels

With its rude and vile inhabitants,

And the Nubia mine is next to them.

They have relationships with each other,

A river separates them. The ends of their land »

For Ibn Majid and the geographers of the time, the "ends of the earth" meet and the three rivers, the Zambezi called Kwama in this quote, and the white and blue Nile are the junction. Thus, as we have seen, in the Ptolemaic geography which the Arab geographers inherited, the African continent bends to the East to close the Indian Ocean. Who is Muna Batur and what is his kingdom? We have no idea about it, but we can think that it is not about Monomotapa, quoted in other places under the name of Munamunawa. Moreover, Ibn Majid knows that it comes from gold and slaves:

Who [Monomotapa] is a mine of men, know it well,

And which is the country of the slave traders, oh my dear!

Ibn Majid does not tell us of amber or ivory in Sofala, but gold and slaves are described there as very abundant. Last interesting point in the description of Ibn Majid, the surroundings of Sofala, whether in the North or in the South, are described as inhabited by vile and dangerous infidels.

Because it is an exposed coast, believe me!

She throws you towards Kwama of the infidels,

Because of this, recognize [the land] in broad daylight

And if necessary, reduce the canvas

Until morning and be vigilant!

According to Ibn Majid, the only Islamized town south of Kilwa is Sofala. We can think that this consideration is not really religious or moral, but that the idea of Islamization here corresponds to inclusion in a commercial network. The “Muslims” are first of all the more or less Islamized regular merchants. Thus Sofala may indeed be the only commercial town south of Kilwa. The author is very virulent with these populations that he considers dangerous. Is it an agreed aversion against “infidels” or societies excluded from exchanges that can play a parasitic role, through piracy for example?

Many cities are shrouded in fantasy and myth, especially when it comes to gold. This text does not give us a precise description of the city, but it describes Sofala, a city integrated into the Swahili world and the main port of gold, in a pragmatic approach to the trade routes of the Indian Ocean, thus giving real consistency to this historical but disappeared object.