The Genetic Make-up of the Elite of the Swahili; Comoros; Madagascar.

----------------------------------

Taken from: Entwined African and Asian genetic roots of medieval peoples of the Swahili coast. Nature nr 615, p866–873 (2023). Brielle, E.S., Fleisher, J., Wynne-Jones, S. et al.

Here we report ancient DNA data for 80 individuals from 6 medieval and early modern (AD 1250–1800) coastal towns; Mtwapa (48 individuals AD 1250 to 1650), Faza on Pate Island (1 individual), and Manda Island (8 individuals AD 1450 to 1650), Songo Mnara (7 individuals AD 1300 to 1800), Lindi (1 individual AD 1500 to 1650), and Kilwa Kisiwani (2 individuals AD 1300 to 1600) and the inland town of Makwasinyi (13 people around AD 1650), about 100 km inland into southern Kenyan. Not all 80 could be used as some samples were corrupted and others were close relatives.

More than half of the DNA of many of the individuals from coastal towns originates from primarily female ancestors from Africa, with a large proportion—and occasionally more than half—of the (male+female) DNA coming from Asian ancestors. The Asian males were already mixed Persian with Indian ancestry, with 80–90% of the Asian DNA originating from Persian men. We find possible Malagasy-associated ancestry in Songo Mnara. Peoples of African and Asian origins began to mix by about AD 1000, coinciding with the large-scale adoption of Islam. Before about AD 1500, the Southwest Asian ancestry was mainly Persian-related, consistent with the Kilwa Chronicle, which describes the arrival of Persians on the Swahili coast and interactions between them and coastal residents. At Kilwa, coin evidence has dated a ruler linked to a Shirazi (Persian) dynasty, Ali bin al-Hasan, to the mid-eleventh century.

Three of the sites (Mtwapa, Songo Mnara and Faza) did not exist as towns in AD 1000, and so the admixed populations moved to those towns later. Thus, the elite inhabitants of Mtwapa and other sites developed from admixed populations and were not foreign migrants or colonists.

After 1500AD, the sources of DNA became increasingly Arabian, consistent with evidence of growing interactions with southern Arabia. The individuals that we analyzed were not fully representative of all social and economic groups in Swahili society. Nearly all of the coastal graves and tombs in this study occupied prominent positions in medieval and early modern towns. With the possible exceptions of Kilwa, Lindi and Faza, we analyzed elite individuals from high-profile coastal sites.

The Swahili states arose out of fishing and agropastoral settlements on the eastern African coast during the late first millennium AD. These sites, beginning in the seventh century, were part of a shared material culture and practice network across the eastern African region. These sites were engaged in the Indian Ocean trading system. Muslims were present from the eighth century AD. A major transition came in the eleventh century, with new settlements and the elaboration of older ones with coral-built mosques and tombs, which was coinciding with the further adoption of Islam. At this time, clearer distinctions also emerged between coastal ceramics and those of inland assemblages. Other aspects of the material culture do show continuity with earlier settlements, including the persistence of crops, domesticated animals, craft styles and ceramics.

Swahili oral histories relates the founding of coastal towns to the arrival of a group known as the Shirazi, referring to a region in Persia. This Shirazi tradition was put into writing in the Kilwa Chronicle in the sixteenth century.

The type of African ancestry needed to make the models fit differed between individuals from the north (Mtwapa, Faza and Manda) and south (Kilwa and Songo Mnara) of the studied region. In Kenya, the best-fitting proxy African source is the inland Makwasinyi individuals who are themselves well-modeled as mixtures of about 80% Bantu-associated and 20% ancient eastern African Pastoral Neolithic ancestry. In Tanzania, the best-fitting African proxy source is Bantu-associated without evidence of a Pastoral Neolithic contribution. Mixing began by AD 1000. We calculated 95% confidence of AD 795–1085 for Mtwapa, Faza and Manda, and AD 708–1219 for southern Kilwa while Songo Mnara from AD 795 - 1085.

Relating medieval to modern Swahili:

We have data for two groups of present-day people who identify as Swahili: 89 with previously reported data (Brucato, N. et al. The Comoros show the earliest Austronesian gene flow into the Swahili Corridor. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102, 58–68 (2018).) and 93 for which we generated new data.

Most of the individuals in the previously published dataset (87 out of 89) have only a modest inheritance from people with ancestry resembling the medieval people that we sampled from nearby coastal areas. However, the newly generated data show a much higher inferred proportion of ancestry from groups similar to the medieval Swahili.

The previously published dataset included people from the coastal towns of Kilifi, Lamu and Mombasa in Kenya who indicated that their family had been Swahili-speaking for the past three generations. The newly published dataset included people from 13 locations along the Kenyan coast who indicated that their ancestors had lived in coastal towns and had a Swahili identity for many generations, thus enriching for more traditional upper-class Swahili people who plausibly retained more ancestry from medieval coastal individuals. The greater medieval coastal ancestry may also reflect isolation. In the newly published dataset from the mainland, individuals from the site of Jomvu Kuu had significantly less medieval coastal ancestry than the individuals from the other sites, all of which were from islands that were plausibly more isolated from admixture with inland groups.

Taken from: Evidence of Austronesian Genetic Lineages in East Africa and South Arabia: Complex Dispersal

from Madagascar and Southeast Asia by Nicolas Brucato, Veronica Fernandes, Pradiptajati Kusuma et al.

2019

Recent results based on genome-wide data from populations around the Indian Ocean rim support the scenario of a “direct route” from Southeast Borneo to the Comoros and Madagascar, as no significant Austronesian gene flow to other Western Indian Ocean populations was detected

(Brucato et al. 2018).

We find strong support for Austronesian genetic contributions in one Somali and one Yemeni individual to their maternal lineages. Timing of admixture is associated with the early Austronesian dispersals but not directly from Southeast Asia but coming from Madagascar. (Identified to carry the Malagasy gene-motif). A second Yemeni individual also carries the Malagasy ancestry but admixture happened only in the 19th century.

These individuals have relatively similar ancestry patterns as the local populations, including a dual Asian ancestry reflected by a South Asian (India) and Southeast Asian (Indonesia) components. Yemenese and Somali do not have significantly more Asian ancestry (0.87% and 1.18%, respectively) than more inland populations. But these two individuals have significantly more Malagasy fragments than are observed in their respective parental populations thus suggesting a likely Malagasy origin of their Asian ancestry.

The age estimate of admixture 1,500–1,800 years BP (Before Present) predates but is consistent with, the earliest Austronesian settlement of the East African offshore islands (Madagascar and Comoros), which is dated to 800–1,200 years BP from recent archaeological (Crowther et al. 2016) and genetic studies (Brucato et al. 2016, 2018).

The results suggest clear, but limited impact, of Austronesian genetic input into these East African and South Arabian regions 0.014%, 2 out of 14,461 individuals with Austronesian key marker.

Note: these 14,461 individuals are the total amount of screened people in East African and South Arabian regions. If a survey was done among the original coastal people whose ancestors lived since many generations undisturbed along the coast or even better on isolated small islands or still better on the remains found in medieval graveyards a way more accurate figure might be found indicating the Austronesian influence in early Medieval times.

Note: As to the written sources:

- Ibn-al Mujawir(1232)(Tarikh al-Mustabsir): People of Madagascar concur Aden.

- Abu Imran Musa ibn Rabah al-Awsi al-Sirafi: Al-sahih min ahbar al-bihar wa-aga’ibiha (978)

He mentions Austronesian people as slaves in Aden and Zeila.

Taken from: The Comoros Show the Earliest Austronesian Gene Flow into the Swahili Corridor

by Nicolas Brucato, Veronica Fernandes, Stephane Mazieres, et al.

2018

On the basis of analyses of genotyping data in 276 individuals from coastal Kenya and the Comoros islands, along with genetic datasets from the Indian Ocean rim, we reconstruct historical populations to show that the Swahili Corridor is largely eastern Bantu. Limited gene flows from the Middle East can be seen in Swahili and Comorian populations. However, the main admixture event in Comorian and Malagasy groups, occurred with Island Southeast Asians as early as the 8th century when they dispersed from this region.

The southern part of the Swahili Corridor, particularly Madagascar, was shaped by the Austronesian world. The Austronesian dispersal was mediated by traders of the Srivijaya Empire (6th–13th centuries). This was centered on the Malaysian Peninsula, Sumatra, and Java islands. In Southeast Borneo, they controlled the important entrepot of Banjarmasin, where they came in contact with local groups. The group who descended from this contact, the Banjar, are currently the closest population to the ancestors of the Asian genetic background found in the Malagasy on Madagascar, 7,500 km away. This migration is also reflected in the Malagasy language, which is closely related to the Banjar language but also borrows from Malay. This contact appears to have occurred during a time of peak activity in the Indian Ocean trading network, most likely after a migration following a direct route across the Indian Ocean. However, the broader history of Austronesian settlement in East Africa remains unclear. The presence of Island Southeast Asians in Madagascar and the Comoros archipelago is supported by archaeological analyses of ancient crop remains, which reveal that Asian species, such as rice, dominated agricultural subsistence from the early stages of settlement on these islands. On the continent, Asian crops were only found at a small number of sites. This suggests that long-term Austronesian settlement could have been limited to these two insular territories. Nonetheless, the two regions also possess important differences, an Austronesian language, Malagasy, is spoken on Madagascar, and a Bantu Sabaki language, Comorian, is spoken in the Comoros. Recent archaeological data suggest that Austronesian settlement might have occurred earlier in the Comoros (8th–11th centuries) than in Madagascar (11th–13th centuries), but the data are limited.

A total of 276 DNA samples were taken from six groups in Kenya and the Comoros islands: Swahili communities from Mombasa (31), Kilifi (93), and the Lamu archipelago (104) in Kenya, and Comorian communities from Anjouan (16), Grande Comore (18), and Moheli (15) in the Comoros archipelago.

This analysis shows that the Kenyan Swahili individuals overlap with other mainland Sub-Saharan groups and that the Swahili communities cannot be distinguished from one another, except for nine Somali individuals, perhaps recent migrants. Comorian individuals fall between the Swahili and Malagasy, the latter group being pulled away from the African pole by their Asian ancestry. Swahili individuals share more genetic material with Comorians than with other continental African groups.

The Swahili populations have one major component (=Bantu) that is also present in other Bantu-speaking groups in Southern Africa. Other minor ancestries are shared with populations from the Horn of Africa and western Bantu speakers. No Asian or Middle Eastern genetic ancestry is distinguishable in the Kenyan Swahili, highlighting the indigenous African origins of the Swahili people. This absence is the main difference between the Kenyan Swahili and Comorians, who do share genetic ancestry with Middle Eastern (6%–7%) and Island Southeast Asian individuals (8%–9%).

Comorians show larger Middle Eastern and smaller Southeast Asian ancestral components than do the Malagasy. The main Swahili ancestry (=Bantu) is shared by both Comorian and Malagasy populations, confirming the previously outlined Swahili genetic continuum.

As expected, significant gene flow from island Southeast Asian populations into the Malagasy (33%–39%) was detected.

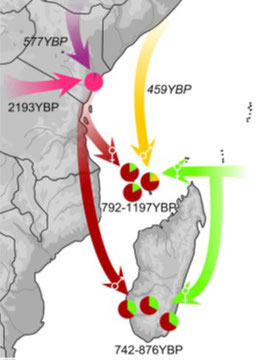

All Comorian communities have a best-fit scenario between a Swahili group (Swahili from Mombasa: 80%–87%) and an Island Southeast Asian group (Indonesian Banjar or Singaporean Malay: 17%–20%) around 792–1197 YBP. Comorians from Anjouan result from a second admixture event between a Swahili group (Swahili from Mombasa: 74%) and a Middle Eastern group (UAE Dubai Arab: 26%) around 459 YBP (95% CI: 35–673 YBP).

All Malagasy groups result from a one-date admixture scenario between a Swahili group (Swahili from Mombasa: 63%–67%) and an Island Southeast Asian group (Indonesian Banjar: 33%–37%) around 742–876 YBP.

Dark red arrows represent Swahili gene flow; light green arrows represent Island Southeast Asian Banjar or Malay; a yellow arrow represents Middle Eastern gene flow; and the purple arrow

represents gene flow from the Horn of Africa. The pink arrow represents gene flow from central and southern Bantu speakers. Dates refer to the last detectable admixture event; dates below pie charts refer to the admixture event between the Swahili and Banjar or Malay. Sex-biased gene flows are represented by male and female symbols in the tip of the arrows; note that they are not present in Malagasy Antemoro and Comorian Moheli.

The Comoros archipelago shows genetic contact between Austronesian (Banjar population from southeast Borneo) and East African peoples around the end of the first millennium. Both Comorian and Malagasy groups derive from an admixture between a Swahili community and a Malay or Banjar group. Remarkably, this Austronesian gene flow is not detected on the African continent or elsewhere in the Indian Ocean rim, confirming that this dispersal followed a relatively direct route toward the Comoros archipelago and Madagascar. Whereas the proportion of the Banjar or Malay genetic ancestry reaches 37% in the studied Malagasy populations and can reach up to 64% in the Highlands, its highest frequency in Comorians is 20%. The earliest detected admixture event in Madagascar occurred during the late 11th century in groups located on the easternmost coast of the island. In the Comoros, it is estimated to be in the 8th century for Anjouan. Also, analyses of ancient crop remains give for Asian crops in the Comoros (8th–11th centuries) and in Madagascar (11th–13th centuries).

Taken from: East Africa and Madagascar in the Indian Ocean world by Nicole Boivin et all. 2013

P45-46

Human Genetics and the Colonization of Madagascar and the Comoros

Studies of Y-chromosome polymorphism and mitochondrial sequence diversity in Malagasy populations have now indicated approximately equal African and Indonesian contributions to both paternal and maternal Malagasy lineages (Hurles et al. 2005). Moreover, in striking confirmation of linguistic interpretations, the closest match to Malagasy Y-chromosomal haplogroup distributions has been found in Borneo (Hurles et al. 2005). The frequency of a Southeast Asian-derived mitochondrial ‘Polynesian motif’ has been shown to be variable amongst different Malagasy populations, appearing at 50 % among the Merina, and only 13 % among the Mikea, for example (Razafindrazaka et al. 2010). The founding Southeast Asian population appears to have been a mixed-sex one: it is estimated that the colonization of Madagascar involved some 30 women, the majority of Indonesian ancestry (Cox et al. 2012). Evidence for an Indian component to Malagasy ancestry has also been revealed, though whether this reflects an Indian stopover on the Austronesian migration route, or a later, independent Indian migration is not yet clear (Dubut et al. 2009). The first studies of genetic diversity on the Comoro Islands have also now been published, and suggest that these islands possess a similar highly mixed ancestry (Gourjon et al. 2011; Msaidie et al. 2011). While the Comoros, like Madagascar, reveal evidence of admixture between Southeast Asian and African populations, however, they also possess a significant western Asian component, reflecting long-term trade links and gene flow with the Arab world. Admixture analysis of the maternal and paternal contributions indicates the gene pool to be predominantly African (72 %) with contributions of 17 % and 11 % from western and Southeast Asia respectively (Msaidie et al. 2011, p. 93). Genetic markers furthermore suggest that the Comoros’ history of gene flow from Southeast Asia is distinct from Madagascar’s (Msaidie et al. 2011, p. 93).