Trade in Cowries: the Old Connection Coast – Interior.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Medievel Authors:

Taken from: (Pseudo) Ibn Al Wardi (about 1456) Kharidat al aji ib (The Pearls of Wonders and the Uniqueness of Things Strange)

Taken from: خريدة العجائب وفريدة الغرائب https://www.minhajsalafi.com/kutub/boldan/Web/3298/001.html

The Nile is divided above their country, at the mountain of Muksim. Most of the natives sharpen their teeth, and polish them to a point. They traffic in elephants tusks, panthers skins and silk. They have islands in the sea, from which they collect cowries to adorn their persons, and they use them in traffic one with another, at an established rate.

Taken from: Ahmad ibn Al Harrani 1300 Egypt; Kitab Djamin al Founoun wa Salwat al Mahzoun (The Book of the Collection of Science and the Consolation of the Sadness.)

There are many people in the land of the Zandj but they have little culture….. It is in this land that the Nile splits close to the mountain al-Maqsam…. From there they go to certain islands, from where they collect shells that they use as jewellery and also sell. There are big kingdoms. Among their towns is Nikand, a very big town… and Ilyanis on the shores of the Zandj sea….. This last town is situated at the end of the Zandj country and its people are idolaters…

Taken from: Wasif Shah: Akhbar al-zaman……al-Ajaib al Buldan (History of the Ages and Those Whom Events have Annihilated) (1209) (sometimes attributed to Al-Masudi)

The sea of Zanj contains several islands where there are various colored seashells, whose inhabitants use them to make ornaments. They bury the teeth of elephants, and when they are moldy, traders from India and Sindh come to buy them.

These Zanj file their teeth until they become very thin; they have large mouths and very white teeth in front, because they eat lots of fish. They have elephants whose tusks they sell to traders from neighboring countries. They own islands where they collect shells with which they adorn themselves, or which they sell. They are divided into several tribes spread among several kingdoms.

Taken from: al Hasan ibn Ali al-Sharif al-Husayni: Mulakhkhas al-Fitan; (book of legal decisions)(1412)

Shaykh Kamal al-Din al-Maqdashi arrived (in Aden) from Mogadishu in 751 (begins 11 March 1350) b.trar y. his ship a chest made of leather (and) there was no payment imposed upon him other then one tenth. Also inside where some cowries covered in leather, but the only payment was one tenth, nothing else.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Coastal Archaeology:

Taken from: Swahili Social Landscapes: Material expressions of identity, agency, and labour in Zanzibar, 1000‐1400 CE by Henriette Rødland 2021

P178

The majority of the cowries came from the survey and excavations on Tumbatu (n=237); only two were recovered in Mkokotoni. The majority of the cowries were Cypraea annulus, although some larger but unidentified cowrie shells were also recovered. A concentration of cowrie shells in trench 2 (the communal room) were recovered in situ below the floor level, probably representing a buried hoard. We might expect that this represents a ritual offering, perhaps related to the use of the room, although the full purpose is not understood. Another hoard may be the 33 cowries recovered from trench 1 (the washroom) in a sub-floor context. Cowrie shells recovered during the survey were concentrated at the centre of the site, which overlaps to some extent with the distribution of the coins. If cowries were used as currency, this pattern may reflect trading activities centred on a specific area of the town. (Tumbatu was inhabited between the 12th and 15th centuries CE.)

Taken from: Swahili origins: Swahili culture and the Shungwaya phenomenon; Allen, James de Vere 1993

There is evidence of other industries in ninth- to thirteenth-century levels at Shanga. Cowries, cone-shells, and other ornamental shells were evidently collected, probably for trade with the interior; and there were shell beads, for which several grinders (designed to smooth their outer edges) also survive.

Taken from: The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks and local developments by John Perkins

At Shanga two hoards of cowrie shells were found next to each other in layers of the first half of the 14th century. This might suggest that cowries were used alongside the coins as a local means of exchange. It might be considered whether the coins, which hardly left the towns in which they were minted, were a local currency as opposed to non-coin money, such as beads and cowries, forming a more inter-regional East African/African currency.

Taken from: Kilwa: A Preliminary Report by Neville Chittick 1966

Taken from: The Swahili Coast and the Indian Ocean Trade Patterns in the 7th–10th Centuries CE

Edward Pollard & Okeny Charles Kinyera

P10

Neville Chittick’s excavations near the Great House and Mosque (of Kilwa) indicated limited external trade in the late 1st millennium CE, determined from the presence of a few sherds of Islamic pottery and glass, ‘very few’ glass beads, carnelian beads, probably from India, and a copper kohl stick. The subsistence economy was based upon fishing, shell gathering, bead grinding and iron smelting. Chittick believed that the large number of shell beads and cowries suggest that they were used for trade. There is no evidence of a mosque or Muslim-type burials.

Taken from: Stringing Together Cowrie Shells in the African Archaeological Record with Special Reference to Southern Africa by Abigail Joy Moffett; Robert Tendai Nyamushosho, Foreman Bandama, Shadreck Chirikure 2021

Very little research into the archaeology of cowrie harvesting or exchange has been conducted along the East African coastline. Preliminary work by Duarte (1993) documented and surveyed a number of sites in northern Mozambique that were located in areas with evidence of contemporary cowrie shell exploitation (Duarte, 1993). Of particular interest was the site of Somana island, in northern Mozambique. Here Duarte noted that a large part of the archaeological assemblage on the island consisted of cowrie shells. Although not dated, relative dates from pottery on Somana estimate it was occupied in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Duarte, 1993: 67).

Taken from: Coins and Other Currencies on the Swahili Coast 2016 Stephanie Wynne-Jones

Several authors have suggested that beads might have functioned as coins. Perkins (2013, 259–62) makes this suggestion for shell/glass beads, purely on the basis of their prevalence on the coast. After substantial excavations at the eleventh- to sixteenth-century site of Gede in Kenya, Kirkman (1964) suggested that cowries might have been used as a currency locally, due to the extremely large numbers found at the site. No locally minted coins were found at Gede, although the site is a densely packed and apparently wealthy stone-town, with deposits rich in imported goods and locally produced ceramics and metalwork. The ‘palace’ at Gede has been seen as indicative of a highly ranked society there, with an ‘audience court’ for a presumed sultan. Cowries also often functioned as beads, and the numbers that had been adapted for this purpose are not recorded. If they were beads, this would not necessarily suggest they were not also currency, but might be further evidence for fluidity between object categories in Swahili towns.

Taken from: L’exxtraordinaire et le quotidien …. By Claude Alibert

In more recent times and marked by an Arab presence, Chittick has not revealed big amounts of cauris in his excavations after the Xth century, in Kilwa (1974) or in Manda (1984: p200).

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Inland Archaeology:

Taken from: L’exxtraordinaire et le quotidien …. By Claude Alibert

And Ricardo Texeira Duarte (1993: p46-47) seems totally confident about the existence of routes to the interior of Africa starting from the eastern coast:

Shells seem to have played an important role in early trade activities in this part of the world. This fact is not only evident from the quantities of shells found on the coastal sites, but also (…) inland. In the site of Broederstroom (…) in Transvaal (…) 5th century, an example of Cypraea or cauril was found (Fagan, 1970) (…) Near the border between Mozambique and South Africa, an example of Cypreaea was found in asite from late in the first millennium (…). In different sites in Zimbabwe, shells from the Indian ocean were found.

Taken from: Wikipedia; Ntusi; Unesco; World Heritage Convention: Ntusi (man-made mounds and Basin).

(At Ntusi village western Uganda) There was also evidence for iron working coming from beads made from ostrich eggshell, fragments of ivory, traces of circular houses, glass beads, and cowrie-shell beads indicating contact with the Indian Ocean.

Archaeological excavations in north-western Uganda have produced glass beads and cowrie shells dating from the 1200s and 1300s (Robertshaw 1999)

Taken from: Stringing Together Cowrie Shells in the African Archaeological Record with Special Reference to Southern Africa by Abigail Joy Moffett; Robert Tendai Nyamushosho, Foreman Bandama, Shadreck Chirikure 2021

P887

The correlation in the timing and appearance of M. annulus cowries and Zhizo/Chibuene series glass beads that came from North Africa/the Middle East via Indian Ocean trade networks has led to the assumption that cowries were sourced and arrived into the southern African interior via ‘long distance trade networks’, in a similar manner to glass beads, in the first millennium CE. Interestingly, while cowries and Zhizo/Chibuene series glass beads do appear together at many sites in the interior, cowries have not been recorded from the early levels of Chibuene (700–1000 CE), presumed to have been the earliest port of trade along the southern East African coastline (Sinclair et al., 2012). The possibility of cowries being sourced from other sites along the East African coastline, and distributed in more dispersed networks, has not been explored.

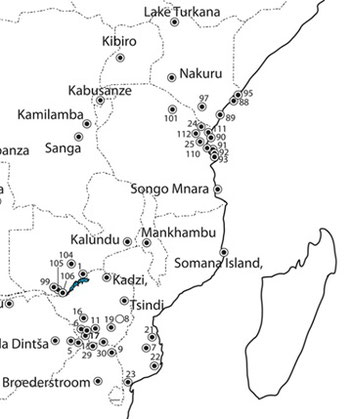

Map depicting some well-known archaeological sites with cowries (M. annulus/M. moneta) from first to mid second millennium CE sites in East Africa. LIST ABSOLUTELY NOT COMPLETE.

1=Ingombe illede, 5=Bosutswe, 6=Jahunda, 7=Manyikeni, 8=Ndongo, 9=Thulamela, 11=Mananzve, 16=Khami, 17=Mapela, 19=Great Zimbabwe, 21=Chibuene, 22=Inhambane, 23=Delagoa Bay, 24=Ngombezi, 25=Old Korongwe, 29=K2 & Mapungubwe,30=Schroda, 88=Lamu, 89=Bajuni, 90=Zanzibar, 91=Fukuchani, 92=Ungujaukuu, 93=Juani, 95=Shunga, 97= ?, 99=Isamu Pati,

101=Ngorongoro, 104=Kalundu, 105=Kumadzulo, 106=Chundu Farm, 110=Muhembo, 111=Tongoni,

112=Kumbamtoni, PLUS ALL THE NAMES ON THE MAP.

P889

Although poorly documented in regional scholarship, cowries, largely M. annulus, occur in a range of archaeological sites dating to the late first millennium and second millennium CE along the East African coastline (Faulkner et al., 2018). In addition, two cowrie ‘hoards’ have been variously documented at the iconic Swahili sites of Songo Mnara (Tanzania) and at Shanga (Kenya) (Haour & Christie, 2019; Horton et al., 1996). Given the proximity to source, cowries have often been overlooked in archaeological research in East African ‘Swahili’ sites as objects that may have held little significance or value to Swahili communities. However, their presence at coastal and interior sites suggests that this assumption may need to be revisited.

Archaeological evidence from the interior of East Africa indicates the early exchange of cowries into the interior. One M. annulus was documented at the site of Kabusanze in southern Rwanda, as part of grave goods in a burial dated to 400 CE (Giblin et al., 2010). Cowries are documented in other archaeological contexts in the Great Lakes region and Central Africa from the late first millennium and second millennium. Wright (2005:113) documented a cowrie from Kathuva (420–653 CE) in the Tsavo National Park, Kenya. These early dates, which predate evidence of contact with wider Indian Ocean trading networks, provide a strong indication that coastal East African communities were exploiting and exchanging cowries inland. M. annulus cowries continue to be found at inland sites in east Africa up until the recent past. Walz (2010) recovered modified M. annulus cowries from sites in the lower Pangani Basin (inland Tanzania) dating to between 750 and 1250 CE. Biginagwa’s (2012; Biginagwa and Ichumbaki 2018) research in Korogwe, inland Tanzania, documented the long history of regional trade from the coast to the interior from the fourteenth century until the nineteenth century (Biginagwa and Ichumbaki 2018: 67). This included the exchange of cowries (M. annulus) through the different occupation phases. Further south, Fagan noted the recovery of three cowries (M. annulus) at the midfirst millennium CE sites of Kalundu and Gundu on the Batoka Plateau in southern Zambia (Fagan et al., 1967a). Fagan (Fagan et al., 1967b: 86) also noted two cowries from Isamu Pati (600–1200 CE). Both were M. annulus with their backs removed. Cowries (M. annulus) were recovered from different areas at Ingombe Ilede (1300–1500 CE) in southern Zambia. ‘In addition, 37 specimens were found with a pair of lion teeth deposited in 2 vessels in level 4 (Cutting SC)’ (Fagan, 1967b: 138). The dorsal surfaces of the cowries were all removed. Further inland, in Central Africa, cowries (species unspecified) were found in tenth- to twelfth-century contexts at Sanga in the Democratic Republic of Congo (de Maret, 1977:324–325). These findings indicate the extensive geographical range within which cowries circulated in inland regions.

Taken from: The Swahili City-State Culture. Paul Sinclear and N. Thomas Hakansonson

P473

But then only a few investigations have been made by Soper (1967) in South Pare and Usambara,

Odner (1911a,b) in Kilimanjaro and North Pare, and Chami (nd) in North Pare. In South Pare, a few glass beads, shell beads, cowries, and copper were found that date to the first half of the second millennium. In North Pare, Chami (nd) made surface finds of a small blue glass bead of unknown date and two potsherds with coastal decorations that date between the 8th and 13th centuries.

Taken from: Swahili origins: Swahili culture and the Shungwaya phenomenon; Allen, James de Vere 1993

Though few such cowrie beads have been discovered inland, a hoard of 210 of them has been reported from the roughly contemporary site (ninth- to thirteenth-century) of Gonja in the Shambaa Highlands (=South Pare). A little ivory was carved for a few chips were found.

Taken from: East Africa and Madagascar in the Indian Ocean world by Nicole Boivin • Alison Crowther • Richard Helm • Dorian Q. Fuller 2013

Marine shell, including cowries (Cypraea annulus) and mitra (Strigatella paupercula), has been recovered from a number of inland localities associated with late first millennium BC PN sites of the Rift Valley, notably Ngorongoro Crater in northwest Tanzania, and Nakuru, Hyrax Hill, Lake Turkana and Tsavo in Kenya (Mutoro 1998; Nelson 1993; Wright 2005). Comparable evidence for the long-distance exchange of marine shell as far as the Great Lakes region has now also been found on some inland mid first millennium AD EIA sites (Giblin et al. 2010, pp. 290–292).

Taken from: East Africa: The Emergence of a Pre-Swahili Culture on the Azanian Coast by Philippe Beaujard

P590

The routes linking the coast to the Great Lakes are known thanks to archaeological data. In the 1950s, L. Leakey discovered a carnelian bead of Indian origin and cowries in a Neolithic tomb in the Ngorongoro crater, dated to the seventh century BCE.

Rock shelters in Bungule, a site in the Taita-Tsavo region in southeastern Kenya, have yielded cowries that were used as ornaments, dated to the beginning of the first millennium (Kusimba and Kusimba 2005: 409).

Taken from: East Africa: The Rise of the Swahili Culture and the Expansion of Islam by Philippe Beaujard

P340

Discoveries have been made along the Tana River, including glass beads, beads made of aragonite, copper chains, and ceramics (Abungu and Mutoro 1993: 703); in South Pare (glass or shell beads, and cowries dated to the first half of the second millennium), and in North Pare (glass beads, and a few shards of coastal pottery, dated to between the eighth and thirteenth centuries) (Sinclair and Hakansson 2000: 473). In the Upemba basin (in the South East of the Democratic Republic of the Congo), west of Lake Moero, cowries have been recovered in tombs dated to the tenth through thirteenth centuries. 35 Tombs belonging to the Classic Kisalian period (Maret 2005: 434). (Classic Kisalian phase (900 - 1200 CE).)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mode of Communication

Taken from: Al Idrisi (1150) (Kitab Ruyar) (Book of Roger)

P58

In the whole of Zendj country the main products are iron and the hides of tigers from Zanzibar. The color of those hides is close to red, and they are very soft. Since they have no pack animals, they themselves transport their loads. They carry their goods on their heads to two towns, Mombassa and Malindi. There they sell and buy.

Taken from: Mohammad ebn Mahmud ebn Ahmad Tusi; 'Aja'eb al-Makhluqat va Ghara'eb al-Mojudat (1160) (The Wonders of Creation)

F. 197.- The people of Zakagi, on an island between the land of the Zang and the Barbar and where the people don’t stop transporting merchandise brought by the merchants.

Taken from: L’exxtraordinaire et le quotidien …. By Claude Alibert

P71

Mark Horton (1987: p89) has as hypothesis that the cauris used the penetration axes of East Africa by which arrived the gold and the ivory. By controlling the distribution of the merchandises in the interior of the continent they (the Swahili) were assured of the monopoly of the commerce in shells, that is cowries and cones.

P72

The cowries must have been utilized for the trade with the exterior. However, John Sutton (1996) says that there are very few cowries in the excavations in the interior of East Africa and Garlake (1973: p132) when talking about the treasure dated to the XIII century found of Great Zimbabwe, affirms:

The objects in the hoard that were readily identifiable as trade imports included two pints of yellow and green glass beads (…) with them were several pounds weight of brass wire and cowrie shells. Although they are known from the earliest Iron Age times, cowries are only very occasionally found on sites in the interior and then only in ones or twos. In a society that did not use them as currency they must have been little valued.

If the cowries, as it was probably the case from the IXth century at least, used the big axes of penetration (and exit) of East Africa, for ivory, gold, etc., it was not to be used as money in the immediate hinterland. The iron bars of Zimbabwe were the money in certain places. But once the real distance from the coast realized, they reached their value. That is why we are trying to retrace those itineraries and to use them as references.

Taken from: The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol 3 by J.D. Fage, Roland Oliver.

P216

Among the local products used for trade to the interior in the period before the thirteenth century, beads made of marine shells must have been important; large numbers of the grooved stone implements used for making these have been found both at Kilwa and Manda. Later, their place seems to have been taken by the imported glass beads. At Kilwa too, in the same early strata, many cowrie shells occur. These become uncommon after the increase in imports of beads and after the introduction of coinage; it seems likely that they were used for trade with the interior rather than as local currency, in view of the fact that they were so easily obtainable. Such was probably also the significance of a hoard of cowries of later date at Gedi.

Taken from: Stringing Together Cowrie Shells in the African Archaeological Record with Special Reference to Southern Africa by Abigail Joy Moffett; Robert Tendai Nyamushosho, Foreman Bandama, Shadreck Chirikure 2021.

P889

The presence of cowries at a wide range of interior sites in East, central and southern Africa from as early as 400 CE gives precedence to the possibility that coastal communities in East Africa were exploiting cowries for exchange in regional networks that linked the coast to interior and different regions of the interior to each other. In fact, this shows a remarkable degree of continuity, under changed circumstances, from the mid-Holocene, when hunter-gather communities in southern Africa were exchanging sea shells with inland communities before the advent of farming (Mitchell, 1996). Although incomplete, our review of the distribution of cowries from first-mid second millennium CE sites in Africa gives strong support to the suggestion that cowries were distributed through a variety of different, dispersed mechanisms rather than through exclusive ‘long distance trade networks’. Similar dispersed evidence of the circulation and consumption of ivory, iron and copper suggests that pre-colonial communities in southern, central and east Africa were linked via extensive nonlinear networks (Moffett & Chirikure, 2016).