This map shows part of the hinterland of the towns Ungwana, Shaka, Mwana. In later centuries (Portuguese times) towns resembling Swahili towns came into existence in this hinterland. They so extended the hinterland even further.

Hudani or Hawadani (Ungwana)

--------------------------------------

Close to modern day Kipini village at the mouth of the Ozi (Tana) river.

Ibn Majid (1470) is the only author to mention it as Hudani and also as Hawadani. There is an unsure mention on the Chinese Maokun map as Menfeichi.

Taken from: Coast-interior settlement and social relations in the Kenya coastal hinterland. By GHO Abubgu and HW Mutoro.

Swahili Monumental Architecture and Archaeology North of the Tana River by Thomas H. Wilson 2016

The ocean comes very close to the western edge of the town. The ruins of Ungwana extending roughly over 45 acres, were first excavated by Kirkman in the 1950s and more extensively, in 1990, by Abungu.

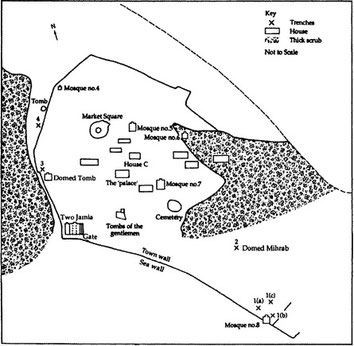

The town was encircled by a town wall which enclosed ruins of eight mosques, numerous houses and several groups of large monumental tombs. Northeast of the town, and adjacent to the town wall, is located a large earthen mound reputed to be the burial place of Fumo Liongo, the Swahili poet-king who is also claimed by the Pokomo people of the Tana basin to be one of them.

The excavations by Kirkman took place at the main mosque the old Jamia(14th-15th century) and the new Jamia (end 15th) (referred to as the Two Jamia -they were build wall to wall), the mosque of the Domed Mihrab, the sea wall and at the gate adjacent to the Two Jamia. Wilson (1978) also opened a sondage near the Domed Tomb, situated close to the mosque of the Domed Mihrab.

For the tombs close to the Two Jamia a date is suggested in the middle of the fourteenth century for the earliest tombs, and late fifteenth century for the later ones.

The divisions of the town are as follows: the palace (central), the central section, the south section, the commercial section, the midwest section, the western, the northern west section, the south-western section, the wells, the town wall, the mosques 1 to 7 and the burial tombs.

The town’s life is divided into six periods, with the beginnings of the settlement dated to the mid-tenth century (Abungu in 1986/7) it lasted until the seventeenth century (Kirkman 1966), when it was deserted.

The area around the settlement, like most of the coastal strip, has fertile soils and enough rainfall for farming to be carried out all year round. The availability of good soils and adequate rainfall could have been one of the factors that influenced the location of the site, for it would have yielded a dependable surplus of food and, in case of scarcity, could have been a reserve for other Tana delta settlements.

Ungwana was well placed to tap the produce of the interior, especially along the lower and mid Tana, with the river serving as a waterway; it was probably a gateway community. Wherever trade is important to the growth of a region, the most influential communities will tend to develop and be situated at strategic locales for controlling the flow of merchandise. These communities flourish at the passage points into and out of distinct natural or cultural regions, and serve as ‘gateways’ which link their regions to external trade. Ungwana, located at the mouth of the Tana (a river that traverses the forested and sometimes arid region of the interior), would have been well suited as a gateway to interior commodities on the one hand and overseas trade on the other.

The wells in the town, which can also be paralleled with others along the Swahili coast, are also similar to some of the inland types and as such are important in the study of the interaction between the coast and the interior, and of the part played by inland groups in the development of the towns. They suggest some architectural influence from the hinterland from areas such as Elwak and Wajir in North-eastern Kenya.

At its peak Ungwana was very prosperous. It was a complex society, with a high occurrence of prestige goods. In the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries AD, the town centred on groups of stone houses with a mosque nearby. At the centre of the town was a large building which appears to have belonged to a wealthy person or ruler of some sort. The structure has been referred to as the ‘palace’.

It ceased to exist as a community in the last quarter of the 17th century due to the advancement of the Galla, an Eastern Cushitic-speaking people from south-western Somalia.

For James Kirkman, Ungwana would be the city of Hoja mentioned by the Portuguese. But for Mark Horton, it would be the city of Shaka which disappears from Portuguese sources in 1637 while the establishment of Hoja is known until 1678. We think that 50 years of difference do not allow such an affirmation, especially since there is an archaeological site at Ras Shaka. The Portuguese attacked Hoja in 1505 and noticed that the city was fortified only on the land side and open on the sea side. The site of Ungwana seems entirely fortified, but the inhabitants were able to build part of the wall after the attack of 1505. (Stéphane Pradines 2014)

End of the Middle-Ages view on Ungwana by the Portuguese.

Taken from: Documentos Sobre Os Portugueses Em Mocambique E Na Africa Central 1497-1840 Vol VIII

ACCOUNT OF THE JOURNEY MADE BY FATHERS OF THE COMPANY OF JESUS WITH FRANCISCO BARRETO IN THE CONQUEST OF MONOMOTAPA IN THE YEAR 1569. By Father Monclaro, of the said Company.

From Malindi we went on to Cambo (1), which is a large town with some buildings, being located on the shore in a narrow passage between it and an island. It has a very good harbour and large naos for trade but sewn with coir. The land is barren and all of sand, being already mainland. The ruler here was a queen, very friendly towards the Portuguese, so much so that she sided with them at great risk. There came to het harbour and town certain galliots and pinnaces of the Turks, who, learning that there were some Portuguese there, asked that they be delivered unto them. Instead of complying, she took them to safety and hid them, wherefore they wrought great damage on the land, taking her and some other Moorish women captive to the fleet; and being by night on the stern of the galliot, she jumped into the sea and swam to safety. And because this queen suffered this trouble on our account, the king who is now with God commanded that all the State of India be put at her disposal, showing her great honour. Francisco Barreto visited het accompanied by a great many soldiers, and in His Highness’s name granted her great freedoms along the coast. It was here that I saw for the first time some trees which abound in India, the roots whereof grow from the top to the ground, and thus they multiply apace. And it is most wondrous to behold how some are already grown into the earth, and others are beginning to become thus attached, and others still grow down, and being so greedy and covetous they would fill everything were they not unencumbered from so many roots. From here we went on to Pate, which was our main destination, with the intention of destroying it for the many evils wrought on the Portuguese in this town. It is about 12 leagues from Cambo (1) along the coast.

(1) Cambo: As it is 12 leagues (12*5.55km) south of Pate it has to be Ungwana which was a large town at a narrow passage between it and an island with a big sandy stretch of land.

Thomas Vernet (2016): The text names the town Cambo, but there is no doubt that it is Lamu because it is specified that the agglomeration is located on an arm of the sea opposite an island and that the soil, not fertile, is entirely made up of sand.

Note: he forgets that it has to be 12 leagues south of Pate.

Taken from: João de Barros; Asia: dos feitos que os portugueses fizeram no descobrimento e conquista dos mares e terras do oriente : segunda década.

P25-26-27

Arriving at the city of Oja (1), which is seventeen leagues (5.55km) from Malindi, which in terms of buildings was similar to Mombasa, but its situation was very different as it was on a river inland, and Oja on the coast of Brava , with a wall on the land side in fear of the Kaffirs , and the reef in the sea , and a difficult entrance that made it stronger, so much so that it appeared, he (Tristao da Cunha) sent a boat to land to notify the Sheikh of who he was, and that he would be enjoying to show him some things, which they bought in the service of the King of Portugal, their Lord. To which the Sheikh replied, that he was a vassal of the Sultan of Cairo, and that without his will, because he was the Sovereign Caliph of the Prophet Mahamed, he could not have communication with people, who so persecuted those who followed him, and even more the merchants from Cairo, who sailed the seas of India: and that in addition to this very common evil, which the Moors had received, he had particularly experienced it in two nations that the Portuguese took from him (2). The reason why this Moor sent such a response to Tristão da Cunha was not so much because of what he said, but because he had been very conscious of defending himself for days, with many Kaffirs from the mainland, his faithful friends, fearing this visitation from the 'El Rey de Malinde due to the differences that existed between them; and also for seeing that the ships, depending on the time, could not be there on the coast for two days, that he could dilute with words, when they were not well received. Tristao da Cunha, because he had also understood the danger of the port, according to what the Moorish Pilots said, who were with him, was in such a hurry, there was a meeting with the captains, who the next day went in the boats to take the land, ……

(1) Oja according to Thomas Vernet (2005) maybe Ungwana. In 1637 when the Portuguese signed treaties with the cities in that area, Oja is not mentioned anymore.

(2) This is the only early instance that is known of a Swahili Ruler having asked the Caliph of being recognized as a Muslim Ruler on the Swahili Coast.

Taken from: João de Barros; Asia: dos feitos que os portugueses fizeram no descobrimento e conquista dos mares e terras do oriente : Terceira década.

p330

…… galleon having such a disaster, in which the Captain, and Pilot, who were to govern it, not daring to go on land, nor wait any longer, due to the great need they had for water, gave the sail their best. They were able to do so, because most of the people were sick, and went to a place called Oja (1), which they crossed twenty leagues (5.5km*20) before Malindi. In which place they found supplies, and whatever else they needed; and there was so much ease in the manner of this communication over a period of days, that the master with five people went ashore, of which the principals were, Simão de Pedrosa, young man from the chambers of the ElRey, and Belchior Monteiro, both natives of Porto, where the Lord of Oja had them for six days, without wanting to let them go to the galleon, showing that he was very happy with their stay, asking them to winter there, where they would be given everything they needed. ……

(1) Oja according to Thomas Vernet (2005) maybe Ungwana. In 1637 when the Portuguese signed treaties with the cities in that area, Oja is not mentioned anymore.