Mombasa

-------------

The earliest authors to mention Mombasa are:

-Idrisi (1150)

-Ibn al Mujawir (1232)

-Ibn Said (1250)

Taken from: MOMBASA Archaeology and History by Herman Kiriama in The Swahili World 2018

Archaeological evidence:

Excavations on Mombasa Island and in town (Kirkman 1974; Sassoon 1980, 1982a; Abungu 1985) have shown that it may have been settled as early as the sixth century CE. A 2001 foreshore survey of the north-eastern part of the island, overlooking Tudor Creek, revealed quantities of TT /TIW ceramics datable to the sixth co ninth centuries (McConkey and McErlean 20107), Rescue excavations by Hamo Sassoon, at the site of Mombasa County Referral Hospital (formerly Coast General Hospital), show that the ancient town may have been located here, an extensive settlement dating from c. 1000 to abandonment or destruction in the early sixteenth century (Sassoon 1980). A more urbanised settlement on Ras Kiberamni appears to have commenced in the eleventh-twelfth centuries, and it is here that Ibn Battuta spent a night in 1331 (McConkey and McErlean 2007). Sassoon's excavations revealed that construction of stone houses likely began in the first half of the thirteenth century (Sassoon 1980), comparable with elsewhere on the coast. Portuguese written sources also show that on three occasions — 1505, 1526, 1589 — Mombasa was destroyed by the Portuguese (Berg 1968: 45), which likely contributed to the abandonment of the old town.

By the Fifteenth century Mombasa residents comprised two confederations, with twelve clans. (A very detailed

Portuguese map of 1725 of Mombasa Island is added as figure 3 other details can be found on the map of 1635 here figure 4. In figure 5 I added the most important historical places of Mombasa

Island to a recent outline of the island and figure 6 adds some more information from 1750). The confederations had independent governments with a tamim or community leader, assisted by a council

of elders (wazee) (Abungu 1985). The first confederation was known as Miji Tisa, made up of nine clans which occupied present-day Mombasa Old Town. Abungu (1985: 3) argues that the clan names

suggest movement of people south from the Lamu Archipelago and the northern coastline, probably during the conquest of Mombasa as mentioned in the Pate Chronicle. The second confederation had

three clans, Miji Mitatu. This group is supposed to have arrived in Mombasa in the late fifteenth, early sixteenth century, settling first at Mtongwe on the southern mainland before moving to the

southern part of the island at Tuaca (Kiriama 1987) (On Tuaca town see fig 2 and 3).

Ceramic finds there indicate its habitation contemporaneous with the later phase of the town, near Ras Kiberamni (twelfth-sixteenth centuries), after which it seems to have been abandoned (Sassoon 1982a: 94). Godhino de Eredia’s plan (c. 1615-1625) designates ‘Tuaca” with a single building, along with a harbor ‘Barra de Tuaca’. A gravestone possibly associated with a ruined mosque in the town bore the inscription '1462° (Gray 1947: 21)(on this tombstone see fig 1). In 2001, a test trench opened by McConkey and McEdean (2007) along Mama Naina Drive revealed remains of coral walls with two phases of construction. Local pottery, glazed green or blue Islamic wares and some Chinese celadon were recovered.

Figure 1: Swahili gravestone of 'Mwana wa Bwana binti Mwidani died 29 Rajab 866AH’ (29 April 1462) Mombasa. The epitaph and border in ornamental Arabic invokes God’s mercy and protection. Hight: 45cm; from Tuaca near Kilindini.

This gravestone is important as it has early Swahili words: 'Mwana wa Bwana’

The dates of Tuaca’s occupation notwithstanding, seventeenth-century Portuguese and German maps show it as a large settlement covered with large trees. The maps also show two pillars: Mbaraki, and a second that was presumably even taller, since fallen. West of Mbaraki pillar (see figure 7) was a mosque excavated by Sassoon in 1977 and Richard Wilding in 1987. From his excavations, Sassoon concluded that the Mbaraki mosque was built c. mid-thirteenth century as part of Tuaca, and in use until the early sixteenth century. After abandonment, the mosque ruin was used for spirit worship, a practice that continues today. Using Portuguese plans of the period as evidence, Sassoon (1982a: 96) thinks Mbaraki pillar was likely erected c. 1700, ‘as a center for consultations with the spirit world, for which purpose it is still used at the present day’. Within the modern community it is thought that the pillar was built by an Omani Arab to thank God for releasing him from the harm of evil spirits; the community regularly burns incense and brings offerings of food and rose water to appease those spirits. Swatches of red, white and black cloth are also hung on an adjacent baobab for similar reasons.

Figure 2: The map gives clearly the town of Tuaca where apart of the anchorage for ships there was also a well for the shipping, a fort and the Mbaraki pillar (visible on fig. 3)

Other features of Tuaca include a demolished ruin of the Kilindini mosque (18th century), also known as Mskiti wa Thelatha Taita (Mosque of the Three Tribes) (Kirkman 1974: 103); the remains of the town wall adjacent to the Likoni Ferry roundabout (demolished to allow for construction of molasses silos), and a concentration of baobab trees.

About the Mbaraki mosque however Sassoon himself writes differently in: The Mosque and Pillar at Mbaraki: a contribution to the history of Mombasa Island. Hamo Sassoon (1982):

The mosque was built about the middle of the fifteenth century as part of the town of Tuaca. It was probably in use from c. 1450-1500. The (very heavy) roof probably fell early in the sixteenth century (which was most probably supported by wooden pillars- who last not more than 50 years- no remains of stone pillars were found) the mosque was then abandoned. It came into use again as a ruin which was used for spirit worship; later the pillar was built for the spirit. The pottery indicates that this must have been at the very end of the seventeenth century. The pots were probably used for burning incense and making offerings of food. A date of about 1700 for the building of the pillar is supported by the evidence of the Portuguese plans which show a ring of trees around the pillar in 1728.

Taken from: Oral Historiography and the Shirazi of the East African Coast by Randall L. Pouwels in History in Africa, Vol. 11 (1984).

Surviving fragments of tradition recall that the original name (of Mombasa) was Kongowea or Gongwa. (Kongowea is now just opposite on the mainland). The dynasty associated with this phase in the town's evolution was pre-Islamic and supposedly matriarchal, being governed by a Queen Mwana Mkisi. Recent excavations indicate that this pre-Islamic phase was roughly contemporary with and possessed a material culture similar to that uncovered in early levels at Kilwa, having first been occupied sometime in the eleventh century. Tradition associates the introduction of Islam with a Shirazi immigration and conflict with Mwana Mkisi, and the subsequent shift of ruling authority to the Shirazi dynasty of a man called Shehe Mvita. Sassoon’s excavations show that the town was Islamized sometime in the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries, a fact corroborated by Ibn Battuta in 1331. The conflict cliche, firm evidence linking the Mvita Shirazi with a greater share for Mombasa in the Indian Ocean trade, the greater wealth of Shehe Mvita's town, the changes in religion and identity involved, and the location of the Shirazi town on the south-eastern half of Kongowea all hint of a steady, controlled evolution through the mechanisms of moiety (=clan) rivalry.

Taken from: Fort Jesus and the Portuguese in Mombasa, 1593-1729 by Charles Ralph Boxer, Carlos de Azevedo · 1960.

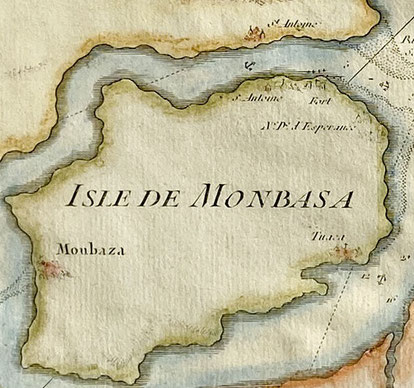

Figure 3: Map of Mombasa Island (1728) by José Lopes de Sá.

1. Chapel of Nossa Senhora da Esperança

2. Fort St. Joseph

3. Fortlet at the end of the ledge

4. Fort of the anchorage

5. Arab pillar

6. Well for the watering place of shipping

7. Palm grove of Kilindini enclosed by a stockade

8. Village of Calangane or of Muscat

9. Makupa fort at the ford of the Mozungulos

10. Two half - ruined Towers alongside the said fort

11. Ford which can be waded knee - deep at low - tide

12. Arab town walled on the land side

13. Houses of Miguel de Faria , used as a factory by the Arabs

14. Custom House of the Arabs

I5. Portuguese factory buildings

16. Wells of drinking - water

17. Church of Misericórdia

18. Convent and church of St. Augustine

19. Fortress ( with Cathedral church inside )

20. Pathways most frequented in the said island

21. Entrance to Mombasa harbor

22. Entrance to Kilindini channel

23. Entrance to the S. António channel

24. Cross used as a landmark for shipping

25. Shoals which must be carefully avoided

26. Land of the Mozungulos

The numbers 4-5-6 together give the place where Tuaca town previously existed.

The number 12 is where Ibn Battuta stayed when visiting in 1331AD

Figure 4: Map of the Mombasa Fortress, Kenya. Bocarro, António. Livro das Plantas de todas as fortalezas, cidades e povoaçoens do Estado da Índia Oriental. 1635

-Above a big Fort Jesus is Tuaca town, the pillar (1700) still not build.

-In the middle of the Island: Kilindini with its palm trees.

-Right of Fort Jesus: the Portuguese settlement with a wall that separates them from the Swahili town. The wall

was built against the attacks of the Mozungullos from the mainland.

-Right end of the island the fortifications to defend against invasion on foot through the ‘ford’.

Taken from: How old is Mombasa? Recent excavations at the Coast General Hospital site. Hama Sassoon. 1976

Between the two ruins of the two mosques no buildings are shown, but the 1976 excavations revealed walls (of buildings at the edge of a town) and abundant pottery here.

At the eastern edge of the excavation site at Mombasa General Hospital walls were uncovered just below ground level with foundations at about 50 cm. The shape of this enclosure and its orientation suggest that it was a mosque. Supporting evidence is provided by a pilaster with cut coral corners in the south wall, and by a cut coral collar which is similar to those used to secure wooden roof supports in the small 15th century mosque at Kaole, near Bagamoyo.

From evidence so far available, it is not possible to be precise about the date of the lowest levels, but they could be earlier than 1200 A.D. The pottery recovered beneath the walls included sgraffiato and "early kitchen wares", indicating that they were built about 1300 A.D. The upper 50 cm of the site probably represent the period 1450-1500 A.D. Possibly the site was already deserted by the time the Portuguese destroyed Mombasa ……… The pottery from the "pre-wall" (=from before these walls at the edge of the town were build) levels bears an interesting resemblance to material from Kilwa and it seems probable that there was regular trade between the two towns in the 13th century. Whereas Kilwa was by then an Islamic settlement, there is no evidence that this was the case in "pre-wall" Mombasa -although pottery from the Islamic world was coming in as trade goods. The building which may have been a mosque is likely to have been built after 1350. From these scraps of information one may guess that the "pre-wall" town was a non-Muslim, and therefore non-Arab, settlement. Possibly the wall-building represents the arrival of Islam soon after 1300.

Hinterland Mombasa

Taken from: The development and collapse of precolonial ethnic mosaics in Tsavo, Kenya 2004 by Chap Kusimba.

In Tsavo national park the hinterland trade of Mombasa was discovered at Kasigau (140km inland from Mombasa): marine shells, ostrich eggshell, and marine and glass beads.

On the slopes of Kasigau mountain in rock-shelters:

Bungule 1 (1047 - 1438 AD) Iron slag, tuyeres, pottery, lithics, shell, glass and bone beads, worked cowry shell, dung, wild and domestic fauna, carbonized seeds, dry stone work.

Bungule 9 (13837 BC - 1640 AD) Stone tools, pottery, shell, glass and bone beads, worked cowry shell, dung, wild and domestic fauna, carbonized seeds.

Kirongwe 1 (722 - 1955 AD) Dry stone work, domestic fauna, glass, shell, and bone beads, Smithing site iron artifacts, tuyeres, forge, pottery.

Kisio (902 - 1955 AD) Lithic and iron artifacts, marine shell, ostrich egg shell and glass beads, pottery, wild fauna.

Taken from: Intersections, Networks and the Genesis of Social Complexity on the Nyali Coast of East Africa by C. Shipton & R. Helm & N. Boivin & A. Crowther & P. Austin & D. Q. Fuller 2013.

Engagement between communities occupying the coastal uplands and those emerging on the low coastal plain is confirmed by the identification of imported goods. These include glass beads from the MIA levels at Mgombani and Chombo, eighth century AD blue-green glazed Sasanian pottery from Mgombani, and ninth to twelfth-century AD Chinese Yue stoneware and eleventh-century AD hatched Sgraffiato from Mteza.

Faunal data from the large 7.56 ha site of Mtsengo (15th-16th century) indicates a growing dependence on domestic livestock over hunted species, with cattle remains forming over 47% of the faunal assemblage and caprines 23%. At the same time, evidence for marine fish and shellfish species suggests access to food products from the coast, a distance of at least 30 km. At the 4.32 ha site of Mbuyuni, (15th-16th century), a shift towards cattle is evident, paralleling the transition at Mtsengo.

A network of economic ties seems to have encouraged the production of a communal surplus for regional exchange. This is illustrated by the intensity of non-subsistence production at Mtsengo. Trade with the coast brought exotic items into the hinterland, for example, a varied selection of imported glass beads were collected from Mtsengo, while Chinese white porcelain (11th or later), Middle Eastern Gudulia water jars (11th-14th) and Islamic monochrome wares (14th-17th) were recovered at Mbuyuni.

Excavated faunal remains from Mgombani (transitional EIA-MIA site: beginning 7th-8th) demonstrate that while transitional EIA-MIA communities kept some domestic livestock, including sheep/goat and some cattle, their subsistence was also dependent on wild mammals. As with the LSA sites, finds of marine shell indicate that these communities accessed maritime environments. Two shell disc beads, and 1 wound oblate and layered Indian red bead were collected.

Excavations have been conducted at two MIA sites in the Coastal Uplands, Chombo and Mteza, both of which have calibrated date ranges between the early eighth to early eleventh centuries AD.

Taken from: The archaeology of the iron-working, farming communities in the central and southern coast region of Kenya BY RICHARD MICHAEL HELM 2000

The Impressive variety of hunted mammals of mainly small to medium sizes would suggest that the communities of Mgombani, Chombo and Mteza were skilled hunters and gatherers.

At the site of Mgombani, a semi-circular arrangement of five post-holes was identified in the early levels of Trench Three. Whilst there was no evidence of any floor, it is possible that this represents the remains of an early house structure, and would thus be the earliest to have been so far identified in the coastal region of Kenya.

Both Mgombani and Chombo had evidence for iron-working, In the form of Iron slag, fragments of tuyere and iron artefacts. Evidence for cultivation was less direct, and was restricted to a fragment of Iron hoe at Mgombani, and a sample of as yet, unidentified burnt seeds from Chombo.

At Chombo special finds included a single shell disc bead, 3 carnelian beads, and 1 wound and 1 drawn glass bead (light green and greenish yellow respectively), and a plain carved ivory 'box'. Gum copal and cowrie shells further emphasised trading connections.

Mtsengo was also seen to have a large quantity of iron-slag. A number of iron artefacts were collected. These included an iron blade, an iron nail, a well-preserved tanged iron hoe, and an iron arrow-head. Artefacts identified at Mtsengo included 7 copper rolls, 3 copper wire coils, 4 copper beads, 2 copper links and 3 other unidentified copper fragments. No evidence for imported pottery, but a varied selection of imported glass 'trade-wind' beads (Davison, C. and J. Clark, 1974), were collected from Mtsengo.

Mbuyuni Very few special finds were collected. Evidence for the production and use of metals were present, all be it minimal. A single piece of iron-slag was collected from Trench One, along with 2 fragments of an unidentified iron artefact. In addition, a copper bangle was collected from the topsoil of Trench Two. Beads, were equally scarce: a total of 3 shell disc beads and a single short drawn light blue glass bead were recovered from the re-deposited spoil of mound two.

At Mbuyuni, only one short drawn, light blue glass-bead was recovered.