Kilwa (Kilwa Kisiwani)

-----------------------------

The earliest mentions of Kilwa are:

- Kitab Ghara'ib al-funun wa-mulah al-'uyun (1050): Kilwalah(?), an island.

- Salma b. Muslim al-Awtabi:in The Kilwa Sira: (+1116)

- Muhammad b. Sa'id al-Qalhati (1200)

.

.

Taken from: Kilwa Kisiwani and Songo Mnara by Stephanie Wynne-Jones in The Swahili World p253-259.

Kilwa and its archipelago:

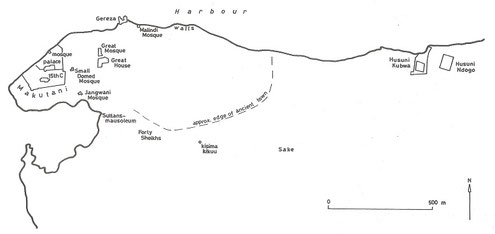

The stonetown of Kilwa Kisiwani developed over approximately 1,000 years, on the northwestern tip of Kilwa Island, immediately facing the mainland. The first settlement of the site is difficult to pin down, but is likely to have dated to the ninth century CE, at which time Kilwa contained wattle-and-daub architecture and was probably a relatively humble fishing and farming community. It is from the eleventh century CE that the earliest stone-built components date: these are limited to the first iteration of the Great Mosque, now preserved as its northern extension, and some tombs in the Sake Cemetery (Chittick 1974: 237–8). Contemporary developments seem to have taken place on the nearby island of Sanje ya Kati, where stone houses may relate to this period. Sanje ya Kati was not a long-lived settlement; the encircling wall, which seems thirteenth century in origin, was built at the tail end of occupation here, before the site lapsed into obscurity (Chittick 1974: 238). In contrast, thirteenth-century Kilwa was experiencing a period of expansion, evidenced first in the construction of Husuni Ndogo. In the early fourteenth century the Great Mosque received the domed extension that makes it such a magnificent monument, and the palace of Husuni Kubwa was built – although never finished – on a bluff to the east of the earlier town. In the succeeding century, stone-built houses, presumably associated with a growing elite, supplemented the townscape. This was also the moment at which Songo Mnara was founded on a nearby island of the same name, containing multiple elegantly built houses and mosques of the fifteenth century, some of which mirror structures at Kilwa almost exactly (Garlake 1966). This would seem to have been part of the same moment of urban expansion and architectural investment, and the two sites should be viewed in parallel. It was also during the fourteenth to fifteenth centuries that modifications of the island coastlines, including stone causeways, suggest the extension of urban territories at Kilwa to include maritime activity (Pollard 2008; Pollard et al. 2012).

Histories:

The historical record relating to Kilwa is one of the richest for the coast. It includes both the indigenous Kilwa Chronicle and a series of mentions by visitors to the region. The names of the sultans mentioned have largely been correlated with names on coin finds from Kilwa and elsewhere; Kilwa was one of the most prolific mints on the coast and Kilwa-type coins survive in their thousands (Walker 1936; Freeman-Grenville 1957; Chittick 1965). The chronicles also contain a wealth of detail relating to the building and occupation of the town of Kilwa. They relate to two dynasties, the earlier Shirazi and later Mahdali, who might also be linked to the major periods of urban development at Kilwa of the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. Ali bin al-Hasan is remembered as the founder of Kilwa, and named as one of a group of six brothers who sailed from Shiraz to found towns along the coast; this narrative is echoed in origin stories across the region. The story of Ali is now thought of as largely allegorical, invoking cultural connections with, and ancestral claims on, the Persian Gulf (Allen 1993; Horton and Middleton 2000). Yet, Ali himself was real, and was one of the most prolific minters of coinage, both of copper and of rare silver issues. Among the Mahdali sultans, al-Hasan bin Sulaiman is particularly celebrated in the chronicles, remembered as a beneficent and pious leader. He was responsible for the construction of Husuni Kubwa, a massive architectural statement unparalleled on the coast. The arrival of the Portuguese at Kilwa in 1505 CE marked the start of its downfall.

Archaeological excavations:

Excavations at Kilwa were on a massive scale, with the clearance of huge amounts of earth that overlay the major monuments and houses. The traces of first-millennium settlement were excavated almost by chance in the environs of the Great Mosque (Chittick 1974: 27).

This archaeological record gave a picture of a rich trading society that thrived at Kilwa from the eleventh century onwards. The numbers of imported ceramics seem to have been surprisingly low. They were not quantified, but seem never to have been more than 1–2 per cent of the total assemblage. Yet, the archaeology of the site evokes the rich, Islamic, connected society described in the histories. Key testament to that is in the surviving architecture and the richest record of imported ceramics is actually cemented into the ceilings of some of the buildings; over 300 Persian glazed bowls adorned the ceiling of the House of the Portico, for example.

Excavations at Kilwa Kisiwani failed to answer some basic questions about the site. One such question (acknowledged by the excavator) is the extent of the former town, which remains vague; the town plan revealed through excavation shows large blank spaces between structures and no evidence for the limits of the town. It is likely that these spaces would have been populated by wattle-and-daub and coral architecture (Fleisher et al. 2012); small test excavations in the area between the main town and Husuni Kubwa have also recovered evidence for metalworking (Chami 2006).

Taken from: Kilwa: A Preliminary Report by Neville Chittick.

(Azania: Journal of the British Insitute of History and Archaeology in East Africa, Vol. 1 (1966): 1-36.)

Period I: pre-Shirazi

Spoon shells are an interesting feature of this phase. They do not occur in later levels. Similar objects, have been found at Talaky and Vohemar in Madagascar.

The first steatite (soapstone) vessels were imported at the beginning of this phase. These objects are imported from Madagascar; they become common in the succeeding period.

Period II: Dynasty of 'Ali ibn al-Hasan (Shirazi)

He introduced coinage, believed to be locally struck. … He is probably to be identified with the traditional founder of the 'Shirazi' dynasty. …. script of this type on coins to be ascribed to the twelfth or early thirteenth centuries, and compares it in particular with coins of the Atabeg rulers of Fars, notably Muzaffar al-Din Zangi, 1162-1175.

Note: however the Stephen Album of Coins puts his coins in the 13th century. While John Perkins (2015) (The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks and local developments) has them around 1100 AD.

Kilwa: Steatite (soapstone) vessels were imported in increased numbers … with a diameter of 20-30 cm. Most with lids, and some with legs, ….. These vessels closely resemble those found at Vohemar on Madagascar. They appear to have been used for cooking.

Period III Mahdali dynasty

The second dynasty at Kilwa, c.1300 onwards. This is the period of extensive building in stone, and the construction of the great palace of Husuni Kubwa is dated near the beginning of it.

Taken from:A PRELIMINARY HANDLIST OF THE ARABIC INSCRIPTIONS OF THE EASTERN AFRICAN COAST By G. S. P. FREEMAN-GRENVILLE and B. G. MARTIN (With the assistance of H. N. Chittick, J. S. Kirkman, and H. Sassoon).

DAR ES SALAAM (NATIONAL MUSEUM)

Commemorative stone from Husuni Kubwa, Kilwa, found in the eastern courtyard of the Great House, probably the epitaph of Sultan Sulayman b. Ish'ia or Isma'il.

Bibl. Chittick, Guide, 10.

Stone excavated at Husuni Kubwa, Kilwa, with an inscription and circular motifs containing Qur'anic quotations.

Bibl. Chittick, "Kilwa", 186-7.

Back and front of marble frieze from a Mausoleum in the Cemetery of the Sultans, Kilwa. Dated 1305-1345. The marble was imported from Gujarat. The decoration is Hindu; so it might have originally belonged to a temple but the borders are inscribed on 1 side 2 rows of Arabic writing; decorated in the center panel with mosque lamps in niches and palm trees,. Gujarat marble was not only found in Kilwa (but also Mogadishu etc..) this shows the great influence of India.

Bibl. Chittick, ARDA, 1961, 3 and pi. lb.

Front and rear from the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin. But other parts in Dar es Salaam

National Museum.

In the Sultan’s palace (Husuni Kubwa) this inscription was found: Verily God is the helper of the Commander of the faithful, al-Malik al-Mansur (the conquering king) al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman, may Almighty God grant him success.

Bibl. Chittick, "Kilwa", 186-7.

Inscription on six pieces of stone excavated at Husuni Kubwa, Kilwa, probably all part of the same decorated frieze, with a text consisting of two rhyming couplets in Arabic, source of quotations not known.

Bibl. Chittick, "Kilwa", 186-7.

KILWA KISIWANI

Epitaph on a narrow stele, partly erased, of Sayyida 'A'isha bint Mawlana Amir 'All b. Mawlana Sultan Sulayman, d. A.H. 761/A.D. 1359-60 or A.H. 961/A.D. 1553-4, in the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin, III E 9687.

Bibl. Reading by M. Jean-David Weill, in possession of H. N. Chittick.

The name: of Sayyida Aisha bint Mawlana is also important as these Arabic words also entered into the Swahili language.

Mawlana or Maulana is a learned Muslim scholar.

Epitaph of Mwana (Miyan) b. Mwana Madi b. Mwana Sa'ld al-Malindanl, d. 24 Muharram, A.H. 1124/3 March, A.D. 1712, from the Malindi Mosque in Kilwa, and now in the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin.

Bibl. Chittick, "Notes", 196-9 and pi. VI; Freeman-Grenville, French, 42-4, discussing the meaning of al-Malindani.

Fragment of an epitaph or an inscription of some size, A.H. 775/A.D. 1373-4, Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin, III, 9692.

Bibl. Reading by J.-D. Weill, in possession of H. N. Chittick.

Lower part of a tombstone made of coral limestone. Found by natives while digging a privy at a depth of approx. 2 m. 35 cm h. 28 cm br. Kilwa Kisiwani

Location: Found 2 m below the 'current' surface by a native while digging a toilet. The top part is still in the ground.

Portion of an epitaph from the Tombs of the Sultans, top half missing.

Bibl. Museum fiir Volkerkunde, Berlin, photograph in possession of Freeman-Grenville, no. 7.

Epitaph from the Tombs of the Sultans, partly erased.

Bibl. Museum fiir Volkerkunde, Berlin, photograph in the possession of Freeman-Grenville, no. 9.

Stele, part lacking, on re-used marble block of Indian origin, with texts from Qur'an, XXXVI, 68-9, and 76-7, from the Tombs of the Sultans.

Bibl. Note by H. N. Chittick; a similar piece, perhaps part of the same stele, is in the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin, III E 6984.

The oldest Swahili documents.

Taken from: The Portuguese and the Swahili, from foes to unlikely partners: Afro-European interface in the early modern era. (Isaac Samuel)

1711AD Swahili letters from Mfalme Fatima; queen of Kilwa; her daughter Mwana Nakisa, Fatima's brothers Muhammad Yusuf & Ibrahim Yusuf (heir). (Goa archive, SOAS London).

They were addressed to Mwinyi Juma a Swahili spy in Mombasa working for the Portuguese and are one of the earliest self-descriptions of the elites of Kilwa as "Swahili" and the Omanis as "Arabs".

This was during a time of political upheaval between the Swahili, Omanis and Portuguese the latter of whom had been expelled by a coalition of the former two, but the Swahili had grown weary of the Omanis of whom according to Yusuf: "...all the coast does not want the Arabs"; while there were promises of cordial relationships earlier between the Omanis and Swahili as stated in Fatima's letter where the Oman sultan had promised: "no Swahili will be mistreated by an Arab" the Arabs did just that, instead; briefly capturing Mwana Nakisa, accusing Fatima of harboring the Portuguese. This explains Mwana Nakisa's very low opinion of the Arabs. Nakisa: "this year, the Arabs who came from Muscat are all scabs, striplings and weaklings".

Yusuf's letter also explains the dynamics of Swahili trade: "this year all the cloth which came from Masqat is on credit and none of it is black, which to us is a deceitful omission, …send us some cloth secretly and we will give him as much in return in ivory".

Taken from : L’ile de Sanje ya Kati (Kilwa, Tanzanie): un mythe Shirazi bien réel Stéphane Pradines

(During the excavation of Sanja ya Kati very close to Kilwa)

Statistically, the proportions of local ceramics are in the majority, which confirms the African nature of a large part of the occupants of the city.

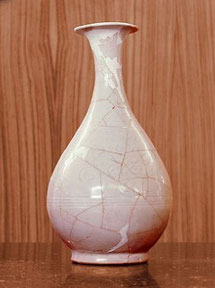

But the most common Islamic pottery in Sanje ya Kati is hatched sgraffiato. Which originates from the coastal provinces of Iran. The Persian hatched sgraffiatos of Sanje ya Kati can be subdivided into two groups, the monochrome brown or mustard yellow hatched sgraffiatos (Kennet 2004, 35-36), which are dated to the late 11th century; and cross-hatched sgraffiatos …... We discovered in the house a large cup of very original hatched sgraffiato. This object, which dates from the end of the 12th century, must have had a certain value because it had been repaired many times.

In the big house, we excavated a layer of waste which contained a lot of Chinese ceramics dated to the Song period, 960-1279. We have identified a few sherds of black and yellow Yemeni, in the level of waste of the house (Pradines 2004, 241), as well as several shards of celadon from the 13th century. Black and yellow are always found in a Mamluk context, precisely from 1250 to 1350. Yemeni black and yellow pottery was produced near Khanfur in the Aden region. This ceramic also called Mustard ware. A fine mustard yellow glaze covers the interior. The latest ceramic material therefore dates from the middle of the 13th century (1240-1250). It was at this time that the flow of ceramic imports changed, and trade with the Red Sea seemed to be preferred. It is also the end of the occupation of the site of Sanje ya Kati.

Taken from: GLASS BEADS AND INDIAN OCEAN TRADE by Marilee Wood (2018) (In the Swahili World).

It is generally accepted that Kilwa was the principal entrepot controlling trade between eastern and southern Africa between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the height of the gold trade from southern Africa. But it is notable that few of the bead types (the Mapungubwe Oblate and Zimbabwe series), found in the hundreds of thousands in southern Africa during this period, were found at Kilwa. Indeed, when Chittick was shown orange beads from Great Zimbabwe, he remarked that he had not seen similar ones on the coast (Chittick 1974: 483). The rarity at Kilwa (and on the entire coast) of bead types that were a key part of trade to southern Africa calls into question the extent of Kilwa’s control over the southern African trade, at least in terms of glass beads.

The Swahili Coast and the Indian Ocean Trade Patterns in the 7th–10th Centuries CE by Edward Pollard & Okeny Charles Kinyera 2017.

This study benefited from fieldwork at Kilwa and Bagamoyo on the Swahili coast, which did not focus solely within the chief settlements but included the surrounding coast and intertidal zone, to reveal areas of trading before large-scale urbanism appeared in the 2nd millennium CE. Furthermore, analysis involved a regional inspection of the imported pottery, glass and beads, combing the research of archaeologists working in Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Comoros and Madagascar, to reveal eastern and southern Africa’s historic trade with the wider Indian Ocean. Fieldwork results thus suggest a less marine-oriented society in parts of the Swahili coast such as at Kilwa, contrasting with a fully fledged maritime society around Bagamoyo in the late 1st millennium CE. The research suggests a relative absence of imported goods in the central section of the east African coast, including Kilwa, in comparison with the more northerly sections of the Tanzanian coast, including Bagamoyo/Unguja and more southerly sections, including around the Mozambique Channel. This study offers a possible explanation of the geographical contrast in import patterns, not only in terms of environmental factors (the influence of monsoon patterns and reliability, which affected the length and safety of voyages in favour of the north; reef dangers particularly noteworthy in Tanzania around Rufiji Delta; and resource availability particularly with respect to gold and ivory, favouring the Mozambique coast), but also in terms of such societal differences as the absence of any significant influence of Islam along the coast south of Qanbalu, LSA (Late-Stone-Age) groups around Kilwa and the presence of Austronesian influences to the south. The latter area may also have been open to a more direct ocean connection with Indian and Far Eastern trading partners rather than relying on the north-western coastal route. A crucial addition to these factors, at least in the Kilwa area, is the apparent juxtaposition of Stone Age and Iron Age traditions, perhaps providing some interdependency and greater self-sufficiency and thus much less integration into the maritime trade system, which influenced areas both further north and at the southern extremity of the east African coast. Much would change in the first part of the 2nd millennium, as Kilwa blossomed into a major city-state founded in part on its entrepot status.

Taken from: The Archaeology of Tanzanian Coastal Landscapes in the 6th to 15th Centuries AD by Edward John David Pollard. 2008